Posts published in 2019

The Global and Local Conversations About Agricultural Conservation

By Kyle Van Rensselaer, ’19, MA ’20

What happens when you pave over a garden? The consequences are fairly small. How about when unchecked urban development paves over tracts of fertile agricultural land?

In a state like California, a major breadbasket for the United States, such changes can threaten food security, land conservation, and farmer welfare. These are pressing issues that the California Department of Conservation’s Division of Land Resource Protection (DLRP) is aware of, and that I was able to help tackle during my Cardinal Quarter in summer 2018.

During my time as a fellow, one of my major assignments was a research project looking into unique agricultural policies in other countries, namely the Netherlands and Israel. My research contributed to a longer white paper that was presented at a UC Davis symposium on climate change in September 2018, which was itself affiliated with the well-known Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco.

The white paper discussed Californian agriculture broadly and paid particular attention to agricultural conservation in the face of climate change. The Netherlands and Israel, as I discovered through my research, are notable because they prioritize agricultural productivity and sustainability in their legal and economic structures, albeit in much different ways.

Despite having a high population density, the Netherlands has an incredibly efficient agricultural sector that invests in innovative practices such as urban rooftop gardens, large-scale greenhouses, and public engagement with sustainable farming. Israel, on the other hand, caught our attention because 93 percent of its agricultural lands are owned and leased out by the central government, creating an interesting dynamic between free-market impulses and traditional conceptions of how national land should be used.

Although reading about these international programs was fascinating in itself, my team and I were most interested in how the policy prescriptions in the Netherlands and Israel could be applied to California law.

In particular, DLRP is interested in expanding and improving its conservation easement program. This program is designed to promote agricultural conservation by bringing farm owners, land trusts, and the California state government together to protect private farmland from development into perpetuity. I was lucky to visit some of the farms that have signed conservation easement contracts and are therefore committed to conservation efforts on their own properties. These visits were a great learning experience because I was able to see how the Department of Conservation builds dialogue with key stakeholders: the farmers who keep California’s agriculture sector alive and running.

The partnership between DLRP and private landowners gave me insights about community engagement and cultivation. Despite political divides, the government and its stakeholders can find common ground and achieve mutually beneficial outcomes.

In particular, many farmers in California support the Republican Party and, as such, tend to be more skeptical of the environmental policies that lawmakers in Sacramento actively pursue. However, DLRP’s conservation easement program has generated buy-in among these farmers because all parties agree on the relevance of supporting agriculture in the long-term.

My research project seemed more relevant when considered alongside these takeaways from the field: while public ownership of farmland, as in Israel, would be a hard sell in the United States, the targeted investments into agricultural sustainability such as those that the Netherlands makes are much more palatable for farmers in the Californian Central Valley. Witnessing DLRP’s role as mediator between lofty policy goals and actual hands-on implementation of farmland conservation was an opportunity to see how the government can bring together diverse stakeholders, and even unusual allies, to preserve a way of life for generations.

Kyle Van Rensselaer, ’19, MA ’20, is an international relations major, chemistry minor, and coterminal student in international policy. He is the historian for the chemistry fraternity Alpha Chi Sigma, head writer for Stanford Chaparral Magazine, a peer chemistry tutor for the Vice Provost for Teaching and Learning, and a member of the Stanford Axe Committee. He is from Auburn, CA.

Beyond the Stethoscope: Addressing the Social Determinants of Health

By Nikki Apana, ’20

For my uncle, no level of mental health treatment could cure his chronic homelessness. No number of visits to the psychiatrist could shield him from the physical and psychological trauma that accompany living on the street. Having witnessed the effects of homelessness on my uncle’s overall wellbeing, I became deeply committed to addressing healthcare disparities through medicine and public health.

At Stanford, I sought out courses that could help me understand my uncle’s experience and how to help. My frosh year I found a Cardinal Course that allowed me to combine my academic interests in public health and passion for public service: Social Emergency Medicine and Community Engagement. In the class, we discussed how socioeconomic status affects health status, and I got to see how these trends play out in the emergency room (ER) through a partnership with our partner organization, Stanford Health Advocacy and Research in the Emergency Department, or SHAR(ED).

The emergency room is a safety net. When people don’t have anywhere else to go, that’s where they end up. Sometimes emergency room patients come in for something as minor as a cold—or a serious condition after a minor condition goes unmanaged for a long time. The hospital ranks the severity of a patient’s condition on a scale of one to five, with one being the most severe. But the ranking says little about the social causes of their illness.

As a volunteer, I screened patients at the Stanford Hospital Emergency Department for social needs that could negatively affect their health. Some of the most common issues included the lack of affordable housing, difficulty accessing a primary care physician, high cost of childcare, lack of healthy food, and difficulty paying utility bills. At the end of each visit, I referred patients to local organizations to help reduce the burden of these needs on their overall health.

I valued providing patients with resources to help them cope with different pressures and reduce the frequency of their visits to the emergency room. However, in medicine there is still a disconnect between physicians and patients: ER physicians are there to only treat serious medical conditions, while patients want any treatment.

During one of my volunteer shifts, I was with a Spanish-speaking patient and a nurse asked if I spoke Spanish. I nodded.

“Oh great! Can you translate for me?” the nurse asked. Then she quickly rattled off a number of test results to me. “Her CT scans, blood test, and everything else look normal. Can you tell the patient that everything is fine and that she should just go see her primary care physician?”

I did as the nurse said. Then, the patient looked at me and asked, “Are you sure there’s nothing wrong?”

From an operational standpoint, the nurse was right; the patient should have gone to a primary care physician instead of the ER. But this patient was like many others in the ER who have never heard of a primary care physician or simply cannot afford it.

As I learned from a young age, addressing medical issues requires so much more than scrutinizing physiological symptoms and abnormalities. Access to healthy food, affordable housing, and high-quality healthcare all contribute to individual health and wellbeing and can prevent frequent visits to the emergency department.

After taking this Cardinal Course, I pursued honors thesis research on the barriers patients face in seeking healthcare—research that I plan to use to advocate for policies that ensure patients’ basic right to high-quality healthcare.

As I look beyond graduation, I hope to apply to medical school and become a primary care physician, with the knowledge that a state of complete health cannot be achieved without remediating the underlying social challenges that patients face everyday.

Nikki Apana, ’20, is a premed student studying human biology, with a concentration in race, ethnicity, social class, and public health. She is a Cardinal Service Peer Advisor, Community-Based Research Fellow, volunteer with SHAR(ED) and, patient health advocate with Cardinal Free Clinics. She is also involved with Kaorihiva, the Polynesian dance group at Stanford. Nikki is from Concord, CA.

A New Yorker Embraces the Urban-Rural Divide

By Hannah Zimmerman, ’21

I could never get over the sky in northern Michigan. One day, standing beside a trailer park after interviewing residents of an affordable housing project, I looked up at the sky. It was so blue and beautiful, and the trees that provided shade for the park residents were so full and lush. The trailers’ taped-up windows and cigarettes smashed into the ground seemed out of place. I looked back down to fasten the snaps on my red notebook, which contained my handwritten notes from interviews with 15 residents of the trailer park.

This past summer, as a research fellow for Stanford’s Anthropology department, I conducted ethnographic field research in Emmet County, Michigan. Emmet County has been unable to adapt to large economic and environmental shifts affecting northern Michigan. There have been massive factory shutdowns: the lumber industry that employed the northern half of the county has been depleted, and thousands of jobs have been lost in the last 15 years. Since 2015, the poverty and crime rates are growing faster than the state average, and 25 percent of the county’s young people have left the area. This area was also the part of the state where my grandmother grew up. Going back was not only a way to explore issues that I had been studying in an anthropology class but to connect with my roots.

In my research, I asked how people in different communities and of different socio-economic groups perceived poverty in Emmet County. This process brought me into lakefront houses and the halls of local government buildings, and—on that day at the trailer park—face-to-face with rural poverty.

Although I had tried adjusting to local customs, the few weeks spent in Emmet County had been a test for me, as I tried to conduct research outside of my comfort zone. As I sat among the trees and going over the interview notes, a man came over and asked if I was okay. I automatically flinched at the sight of his gun, perched in a holster on his belt. Growing up in New York City, carrying a weapon openly is illegal; the only interaction I had with firearms growing up was watching them used as weapons in movies. A few weeks earlier, a shop owner told me that I should just assume people have a gun on them and be surprised when they don’t. In both small and big ways, I saw how different my worldview was.

Rural poverty was nothing like the poverty I had observed in my home of New York City or in the other cities where I had worked. Rural poverty was spread out and generational. According to many residents I interviewed, the idea of getting out of poverty didn’t seem at all possible. In fact, after cross-checking all 15 interviews, I found that no one who spoke to me thought they could get out of poverty legally. This was a side of America, of poverty, that I couldn’t have imagined existed or would have been able to truly understand by reading articles about it written by New York- or Washington, D.C-based news outlets.

As an anthropology major, you’re asked to consider your own perspective as well as the perspective of others in order to understand complex issues. The rural fieldwork was challenging but it was a powerful introduction to thinking about issues from both an urban and rural perspective. This is important as I continue to work in national politics, because understanding the rural-urban divide is key to enhancing democracy at varying levels of government.

When I returned to campus this year, my friend and I have continued discussing the urban-rural divide: she, someone from rural Illinois and who worked in Washington D.C, and I, a New Yorker who worked in rural Michigan. Together, we are co-writing a piece about this divide and how we understand each other, and this is challenging us to confront our own biases.

Hannah Zimmerman is a sophomore majoring in public policy and anthropology. In summer 2018, she worked as a research fellow in Stanford’s Department of AnthropologyMichigan. She was involved in the Haas Center’s Public Service Leadership Program and has served on Stanford Rural Engagement working group as part of the University’s Long-Range Planning. She is currently a co-chair of the Stanford Student and Labor Alliance, and Stanford Coalition for Healthcare Reform. She is from New York City.

Music, Laughter, and Joy: A Summer of Therapeutic Music in Senior Living Communities

By Samantha Starkey, ’19

Research shows that singing has beneficial effects on the mood, cognition, and health of older adults. These findings are the basis of my placement organization last summer, SingFit, a Los Angeles-based startup that uses technology to make therapeutic music more widely accessible for older adults. During my time interning with SingFit, I saw how one-on-one and group therapeutic music sessions in senior living communities enhance the well-being and social engagement of older adults.

At one of my group sessions at a memory care facility, there was a gentleman who at first seemed confused and disgruntled.

“I can’t sing. I don’t know the words. I can’t even hear properly,” he complained.

As time went on, he began singing along with the group, and he would suggest songs from musicals like West Side Story, once gracing us with a brief rendition of “Maria” in a mellifluous tenor voice.

One day, we sang the Andrews Sisters song, “Beer Barrel Polka.” Most songs have associated dance moves to encourage movement, and we all repeated the “Beer Barrel Polka” move throughout the song: pretending to drink a mug of beer. Afterward, with a deadpan face, he looked at me and mock-sternly cried, “You’re over your limit!” The whole group giggled.

That gentleman was just one of the many people who had a profound impact on me this summer. Working with him made me realize that patience, respect, and music can bring out talents, humor, and joy in people.

Sam Starkey is a senior studying human biology and education. Samantha served as a Roland Longevity Fellow with SingFit. At Stanford, she has been involved in several Cardinal Commitment student organizations, including Side by Side, The Bridge, and Ravenswood Reads. She is from Vancouver, Canada.

Organizing alongside the ‘Beloved Community’: Police Accountability from the Grassroots

By Evander Deocariza, ’20

This summer I completed a Cardinal Quarter with PACT (People Acting in Community Together), a multiracial, multi-faith grassroots organization based in San Jose, CA. PACT has a small staff of about 10 organizers who empower people around Santa Clara County to fight for housing justice, immigration justice, and law enforcement transparency and accountability within their communities. Rather than speak for community members who are most directly impacted by policies, PACT teaches them how to build power and take action in the public arena for themselves.

Through PACT, I had the opportunity to learn by doing. I primarily worked with the organization’s Beloved Community team, which focuses on issues of police accountability. We met with city officials and coordinated a media campaign that successfully convinced San Jose’s mayor and city council to pursue an ordinance expanding the Office of the Independent Police Auditor, which independently investigates policy misconduct complaints. I also worked one-on-one with community leaders to help them develop the skills and tools to conduct their own research into policing policy reform.

Working at PACT changed my understanding of what a good organizer does. Initially, I conceived of an organizer’s leadership through the lens of my military experience. After serving five years in the Marine Corps as a cryptologic linguist, I was very used to working within a hierarchical structure. In the military, there is a clearly delineated chain of command, and orders come from the top. Leaders are responsible for creating a plan, issuing orders, and supervising subordinates to ensure those orders are carried out. With this idea of leadership in mind, I thought an organizer galvanized a community and delegated tasks for others to carry out as part of a strategic plan that they formulated.

The language PACT uses to describe roles suggests how very wrong I was: paid organizers are referred to as “staff,” while the community members who volunteer to work on issues are called “leaders.” I learned that organizers teach leaders; leaders organize. That is, staff teach and guide leaders in developing skills like how to schedule meetings with public officials, how to chair meetings, how to publish Op-Eds, etc. Organizers work in the background to enable community members to speak and act for themselves.

Though I don’t see myself as particularly well-suited for a career in organizing, I now understand how people power is generated through organizing. I appreciate its potential to create lasting, societal change from the ground up.

Evander Deocariza, ’20 (Computer Science), served in the U.S. Marine Corps from 2011-16, and transferred to Stanford from San Diego Mesa College in fall 2017. Evander was one of more than 500 students to complete a Cardinal Quarter in summer 2018.

Launching The A(bilities) Hub Initiative

By Zina Jawadi, ’18, MS ’19

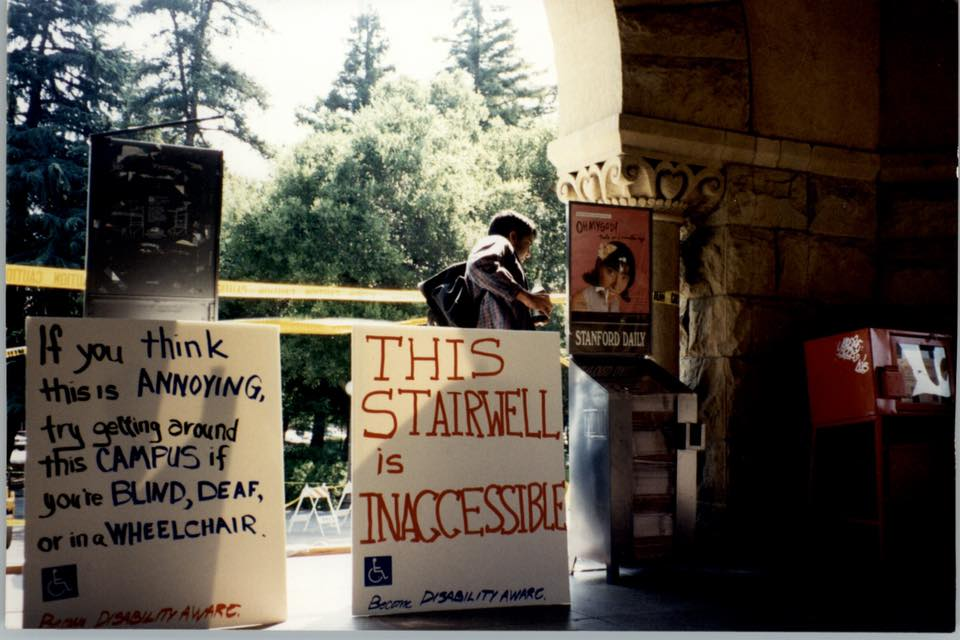

Disability advocacy efforts have been vibrant at Stanford for decades, and over the past few years, students with disabilities have resumed advocating for a disability campus center.

In 2013, Vivian Wong, ’12, realized that there was no disability community space or student organization at Stanford for students with disabilities.

She helped create a new position in the ASSU Executive Cabinet and worked with Krystal Le, ’14, to found Power2ACT, a much-needed student organization that provided a safe space for students with visible and hidden disabilities.

When I arrived at Stanford in 2014, I saw that people with disabilities still lacked a physical space. I had just worked with my high school’s administration to found a disability awareness program and thought I could draw on this experience to help make a meaningful impact at Stanford.

I am a member of several minority groups as a hard-of-hearing, Iraqi American, second-generation immigrant. My passion for disability advocacy began in the eighth grade, driving me to compete in more than 30 Original Oratory competitions and to join the Hearing Loss Association of America, California State Association. At Stanford, the skills from my nonprofit board involvement and my public speaking experience came in handy.

During my sophomore year, former Power2ACT president and ASSU Executive Cabinet member Chris Connolly, ’15, and Kartik Sawhney, ’18, reached out to help me revive the pursuit of a campus center with the ASSU Executive team. Together, we communicated to students, faculty, and administrators about the need for a physical space on campus.

I am often asked why it is important for a community to have physical space at the Farm. A physical space will allow students without disabilities to think about disability, increasing the visibility of disability and emphasizing the disability community’s place at Stanford.

In November 2017, the A(bilities) Hub Initiative was launched in conjunction with the 2017-2018 Disability Awareness Week. We were appointed an official staff advisor, Carleigh Kude, and established a student-led committee for the A-Hub.

In launching the A-Hub, I discovered the many paths that our members take to join our community, including advocacy, disability studies, personal reasons, or a family member’s experiences. Working with them, I learned how a few individuals with shared advocacy goals can make a community stronger and that unifying individual efforts can multiply the effects.

Currently, the A-Hub is a temporary space, and we are still working toward a long-term solution: an established community center with a full-time director.

Zina Jawadi is a student advocate for disabilities rights at and outside of Stanford. Zina supported the launch of the Abilities Hub in 2017 and the formation of the Stanford Disability Initiative in 2017, for which she continues to serve as co-chair. Zina was the president of Power2ACT in 2016-17 and was an ASSU Executive Cabinet member in 2016-17 and 2017-18. Outside of Stanford, Zina is active in the Hearing Loss Association of America – California State Association, serving as board member since 2013 and president since 2015. Zina is a member of the Haas Public Service Honor Society. She is from the San Francisco Bay Area.