Posts published in 2020

Revisiting Milwaukee: Learning About My Hometown Through Service

By Elyse Cornwall, ’22

The first time I drove to Moody Park, I suppressed my nerves about driving into an area known for reckless driving. I reminded myself that these feelings came from racist assumptions about a community I had never meaningfully interacted with. Still, I stopped at green lights as oncoming cars ran the red, and rushed down main streets to keep other cars from skirting past me. Thus, I arrived at Moody Park feeling simultaneously afraid and embarrassed, and that was when the youth participants arrived. My primary responsibilities were event planning and coordinating with other volunteers, but I realized that my work behind the scenes could not be effective until I immersed myself in the community I served. When I ate meals, played games, and shared stories at Moody Park, a new side of my service experience emerged.

My weekly discussions with youth living near Moody Park covered topics like drugs and alcohol, police relations, and reckless driving. The group’s familiarity with dangerous situations seemed to contradict their charisma and friendliness. I helped host the Zeidler Center’s listening circle events, which allowed youth and police officers from the area to talk with each other in small groups. The youth took turns responding to prompts such as, “Describe an experience you have had with a police officer,” sharing their experiences rather than debating or convincing anyone. The Zeidler Center hosts listening circles like these throughout the Greater Milwaukee Area, featuring topics like political polarization, race relations, and education. These events are based on the organization’s belief that open, respectful dialogue promotes positive change. I watched as the listening circles at Moody Park shifted from short responses to candid conversation. By the end of the discussions, youth and officers were sharing accounts of their days and stories of hardship, relating to one another on a personal level.

As an outsider in this community, I felt hesitant to expand beyond my role as a staff member, but eventually gave in with the encouragement of the youth and other staff. I shared my own experiences, admitted the gaps in my knowledge of Milwaukee, and put myself in a position to learn from the youth I had aimed to serve. Not only did I feel more connected to a community that I hadn’t interacted with before, but I also felt a stronger obligation towards my city. I found that my view of civic duty and participation changed once I got to know the people with whom I was sharing a community.

By the end of the summer, I started to see my service experience in connection to my parents’ work in Milwaukee as public servants. Usually, I thought of my parents as lawyers who happened to work for the state and county. Though they had expressed pride in serving those who relied upon public legal assistance, I never thought of their occupations as reflections of their character. As a court commissioner, my father has the opportunity to combat the racial bias that targets people with his racial identity in most courtrooms. Like my father, the staff and volunteers at the Zeidler Center prioritize listening to and learning from the communities they serve.

I am glad to have developed this new civic understanding in the context of Milwaukee, through the service I have done. When I returned to Stanford in the fall, I brought with me a willingness not only to serve, but also to know the people within my community who are most targeted and misrepresented.

Elyse Cornwall, ’22, studies computer science at Stanford. Originally from Milwaukee, WI, Elyse completed a Cardinal Quarter in her hometown the summer after her freshman year, working to support the Zeidler Center, an organization that fosters civil dialogue across perspectives. At Stanford, Elyse is a CS106A section leader; a team leader for Ideas Out Loud, Stanford’s TEDx club; and a member of the Delta Delta Delta Sorority.

Flying Solo at the Santa Lucia Conservancy

By Max Klotz, ’20

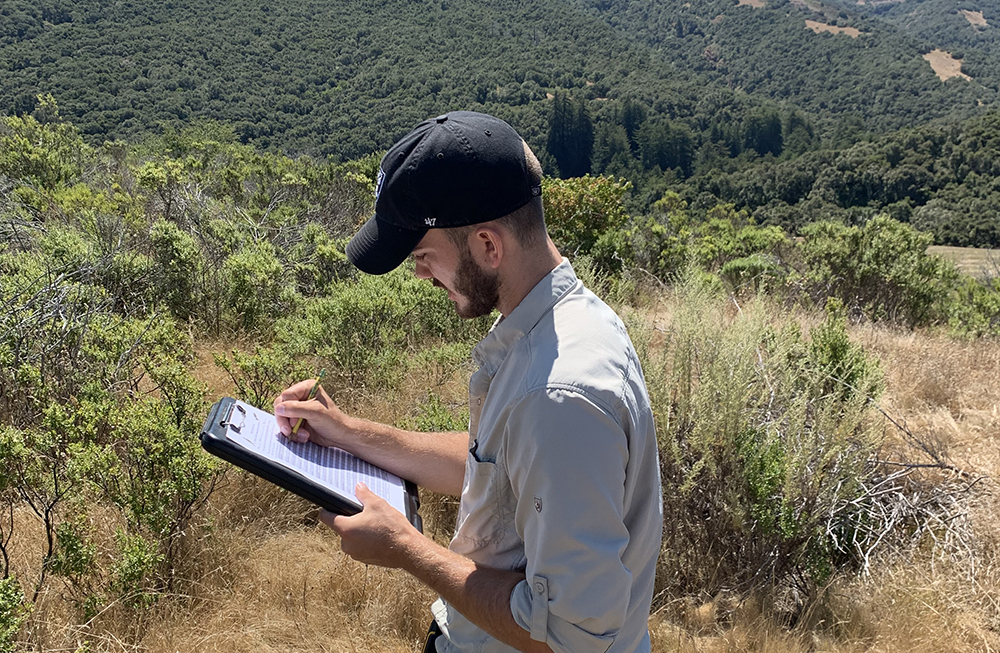

When I made it to the trailhead, Hall’s Ridge was still blanketed in mist. I couldn’t see 15 feet from me, let alone the views down into the valleys on either side of the ridge. I used the delay to organize my photos and make sure I knew the location of each photo point, places with distinctive landmarks that could provide a record for evaluating vegetation changes over time.

The morning mist quickly gave way to sun as, seemingly in minutes, the fog layer around me burned off to reveal views all the way to Monterey Bay. Now having the visibility necessary to capture my photographs, I set off on the trail. I spent the rest of the day hiking and taking pictures, not just of my photo points, but also of the hawks and vultures that circled by the trail.

My project at the Santa Lucia Conservancy in Carmel consisted of selecting and replicating historical photographs of the Santa Lucia Preserve to show the land’s changes over time as part of broader ecological conservation efforts. The process for obtaining repeat photographs of each historical picture was intricate. First, I had to carefully select historical photographs that featured distinctive landmarks in the preserve. Then I worked with my supervisor to identify the approximate locations of each historic photo point and map them using waypoints on the MapItFast software. Finding the exact location for each historical photograph and taking current pictures with the same framing were the final and most challenging steps. I had been struck by the beauty of some of the historical photographs on Hall’s Ridge, so I was excited to explore the area. Early on in my internship at the Santa Lucia Conservancy, I had mostly explored the preserve with other employees, but as my project progressed, I came to enjoy the meditative nature of the days I spent on my own. I set out in a company truck with my water, lunch, camera, and stack of historical photographs. Several weeks into my project, I began to make my way around the different photo locations on the preserve to capture what those photo points look like now. In the process of driving and hiking from place to place in search of historic photo locations, I started to become familiar with the land and its intricacies.

As I looked at my photographs at the end of the summer, I realized the project had shown intriguing results. There had been dramatic changes in some areas of the preserve and a dramatic lack of change in others. Through photography, I was able to track brush encroachment on grasslands, lands recovering from fire treatment, and other broad changes over the course of decades.

This hands-on Cardinal Quarter experience has given me an understanding of the power of combining ecological studies with creative work, as well as a desire to continue to use these tools throughout my career.

Originally from Stanford, CA, Max Klotz, ’20, studies human biology with a concentration in environmental studies. Max completed a Cardinal Quarter during the summer of 2019 with the Santa Lucia Conservancy in Carmel, CA. In addition to engaging in a range of hands-on conservation activities, he helped develop a project to reproduce historical photographs of the Santa Lucia Preserve in order to document environmental change over time. View his “Repeat Photography” project on the Santa Lucia Conservancy website.

Redesigning Justice: Transforming Housing Courts to Housing Centers

By Leya Elias, ’21

Only at Stanford could I take a class that allowed me to use legal design to create and test innovative solutions to a pressing challenge in my hometown: homelessness.

In the summer of 2019, I interned with the Public Rights Project, where I learned about the under-enforcement of consumer protection laws and the cracks within the civil justice system. After leaving my internship, I craved an opportunity that would teach me more about the civil court system, while also allowing me to work alongside community members to make improvements where needed. Luckily, I found a Cardinal Course called LAW806Y: Justice by Design: Eviction and Debt Collection. This course gave me the opportunity to explore my interests in civil courts and economic justice through a legal justice lens and design-thinking practice.

Through the class, I got to work alongside a community partner, the Judicial Council of California, and spend time learning from people—community organizers, attorneys, court staff, policymakers, landlords, and tenants—who have all touched the eviction system, for better or for worse. One stark injustice that consistently came up in all of our interviews was the disparity in access to legal representation in the court system and how, as a result, many tenants face little chance at avoiding an eviction.

While the majority of tenants do not have access to attorneys, over 60 percent of those who do are able to successfully avoid evictions. Access to legal representation is a huge unmet need for populations most at risk for homelessness. In addition to the inaccessibility of civil legal representation, tenants experiencing eviction are not only at high risk for homelessness, but are also missing a centralized support system dedicated to their success and well-being.

Since 2018, homelessness has increased 17 percent and 43 percent in San Francisco and Alameda, respectively. Witnessing the changes in my own city, I became interested in how the court could serve as the center of preventative support systems for not only those experiencing evictions, but those at risk for homelessness. Through the course, I had the opportunity to work on a facilitated holistic social services and legal aid program based in courthouses that offers resources such as rental assistance, skills training, and relocation programs.

As I work on testing my prototype alongside community partners and the Judicial Council of California, I am motivated by the potential for this program to decrease the rampant displacement across Bay Area communities. As a new family member or friend experiences eviction, displacement, or homelessness, the work I am doing in this class becomes even more pertinent and leaves me feeling honored to be able to think about how I can help.

Before the class, I saw becoming a practicing attorney as my only path toward mitigating the inaccessibility of legal representation. However, the course’s application of design-thinking to legal systems has equipped me with an innovative toolbox with which to approach systematic legal issues as an attorney. As I look forward to my senior year, I am excited to take this new experience of social justice-oriented design-thinking to my work in and out of the classroom. I am empowered not only to become an attorney, but to become an attorney capable of redesigning our country’s legal system into one that works for our most at-risk communities.

Leya Elias, ’21, grew up in San Francisco, CA. At Stanford, she studies psychology with a minor in political science and African & African American Studies. Leya completed a Cardinal Quarter in summer 2018 with the Ghana Center for Democratic Development and worked with the Public Rights Project in Oakland, CA during summer 2019 with the support of Emerson Collective. Leya is co-president of the Stanford Ethiopian & Eritrean Students’ Association and the Stanford Black Pre-Law Society, and has served as chair of the ASSU Undergraduate Senate as well as an Institute for Diversity in the Arts fellow.

Policymaking by Empathy: Interning at the State Department

By June Lee, ’21

It’s 8:10am when I walk into the office, my blouse lightly dampened by my walk under the merciless Washington, D.C. sun. As I head to my cubicle, I hear snatches of conversations on the humanitarian crisis in Yemen and the current status of peacekeeping in Mali. I can’t help but feel a secret thrill to be working alongside individuals on issues I’d only ever read about and studied in classes.

Interning at the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Conflict Stabilization Operations was, academically, one of the most enriching experiences I’ve had. Through weekly meetings, I gained exposure to the incredible breadth of concerns incorporated into the United States’ conflict stabilization efforts, from the role of women in peace processes, to the importance of intra-group cohesion in negotiations, to the efficacy of interventions by nonprofits and other third parties. No matter what project I was working on, it was fascinating to realize that here, my efforts could have a direct application for policy. Translating an article evaluating violence reduction in Colombia could directly inform the bureau’s engagement with partner organizations on the ground. Similarly, developing a digital framework on Excel depicting election violence indicators could help the bureau allocate funding and resources quickly to mitigate the risks of political violence. Over time, I also gained familiarity with the inter-agency process and overlapping departmental structures responsible for developing and implementing U.S. foreign policy.

Yet the most valuable thing I learned from my internship was the incredible depth of empathy it takes to work as a public servant in the State Department. The individuals I encountered worked on projects that directly affected the welfare of communities in countries emerging from conflict, and they were constantly thinking about the communities they were seeking to support. This mindset translated to all aspects of their work. My main supervisor related how, while serving as a foreign service officer in New Delhi, he would often bike to work with a camera, and offer to take pictures of people on the street. Their surprise and joy upon receiving a picture of themselves led to his receiving a flurry of texts and blessings every holiday. Another director, frustrated with the United States’ failure to address the humanitarian crisis in Syria, was motivated to resign and work for a nonprofit focused on human rights advocacy for Syrians and other refugees. And, during my daily commute, another officer explained how he had worked in Afghanistan for 18 years, an experience he spoke of with a hint of sadness but also admiration for the resilience of the Afghan people.

Since my internship, I’ve been determined to embrace this mindset. As a director of Stanford in Government and a peer advisor in international relations, I’ve sought to encourage more students to pursue careers in policy and public service. And, while working on my senior thesis, I am committed to developing a research paper that can be beneficial to policymakers and useful in advancing the United States’ efforts in conflict resolution.

Originally from Sunnyvale, CA, June Lee, ’21, studies international relations at Stanford. In addition to completing a Cardinal Quarter summer fellowship with the State Department’s Bureau of Conflict Stabilization Operations in the summer of 2019, June serves as the director of diversity and outreach of Stanford in Government and as a peer advisor for the international relations department. June is also an incoming honors student with the Freeman Spogli Institute’s Center for International Security and Cooperation.

My Most Important Lesson

By Thomas Allen Wehner, ’20, MS ’21

When I first started as a tutor with the High School Support Initiative (HSSI) freshman year, I didn’t realize the depth of the program and how much it would mean to me. I signed up after getting an email about the program because I liked tutoring and it sounded like a good cause. I joined HSSI as a tutor going out to my school site once a week. I was barely aware of the complexities of the program, the intricacies of ethical service, and the depth of how my identities interacted with the complex histories and systems at play in the education system. I had a lot to learn.

At the end of freshman year, I became an HSSI fellow and spent the next three years working with and learning from the incredible team. As a fellow, I was part of the program staff, with expanded responsibilities to support the tutors and program. As a team, we worked with Stanford students, analyzed feedback, hosted workshops, discussed articles and program changes, filled in spreadsheets, tracked attendance, and went out every week to maintain our anchor in the most important work by tutoring high school students.

This experience sparked my interest in education, organizational behavior, and nonprofit work. I had joined HSSI because of its focus on working with high school youth, but working as an HSSI fellow helped me discover that I was even more interested in learning how to develop the organization and volunteers to better serve and collaborate with youth and community partners. This insight helped guide my future plans, highlighted what talents I have to use in collaboration with others to build a better world, and revealed what skills I still need to develop.

Every experience with HSSI pushed me forward as a person – whether building facilitation skills with volunteers, learning the power and shortcomings of the Principles of Ethical and Effective Service, or better understanding how to be an ally as a person of privilege in the fight for educational equity.

The time I spent with the HSSI team added so many dimensions to my Stanford experience, and I consider it to be the most important part of my education here. Beyond fostering a set of technical skills, this experience helped me learn about myself and understand my journey to being a better friend, ally, coworker, volunteer, leader, and person. I am forever grateful to Sophia Kim, our wonderful program director and mentor, and the rest of the HSSI family for this incredible experience.

Originally from Highland Park, IL, Thomas Allen Wehner, ’20, MS ’21, studies electrical engineering at Stanford. In addition to serving with the High School Support Initiative (HSSI) for all four years of his undergraduate career, he has been involved in the campus theater scene, most recently as the executive producer of Ram’s Head.

Unequal Treatment: Exploring Unconscious Bias in Health Care

By Nikki Apana, ’20

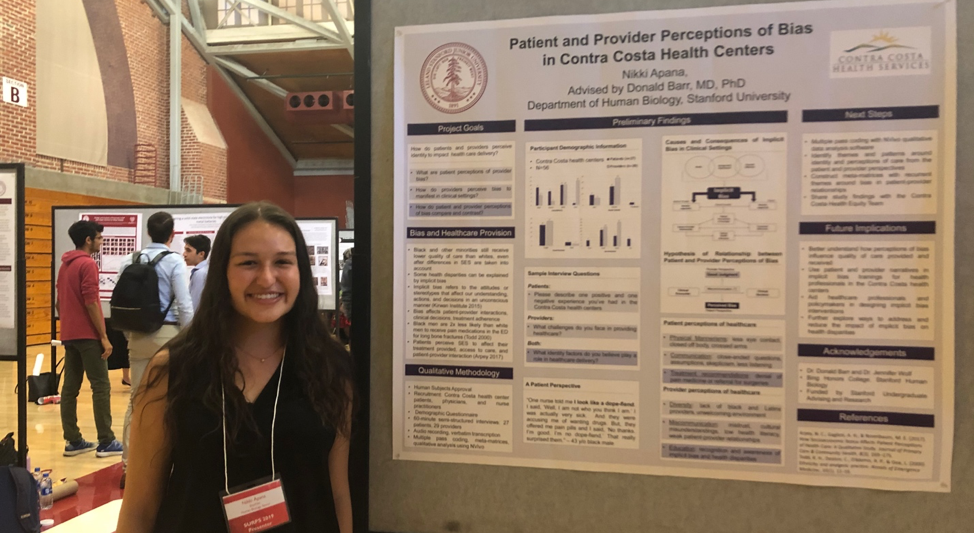

“One nurse told me I look like a dope fiend. I said, ‘Well, I am not who you think I am.’ I was actually very sick.… And they were accusing me of wanting drugs.” – James (pseudonym), 43-year-old Black male

James is a participant in the community-based research project I have been conducting over the past three summers. I have been collaborating with Contra Costa Health Services, the public health system in my hometown, to find ways to address unconscious bias in patient care. Unconscious bias refers to the stereotypes we internalize that affect our behavior, judgments, and actions without our conscious awareness. And what is so pernicious about unconscious bias is that everyone has it, yet few realize it.

Unconscious bias covertly plays out in our everyday lives. As described in Howard Ross’s Everyday Bias, NBA referees call more fouls against Black players than White players, famous Black actor Danny Glover reported struggling to hail a New York City cab after dark, and job applicants with “Black” names are less likely to receive a callback than applicants with “White” names. Bias extends beyond race to gender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, age, and weight. It surrounds us every day and it is embedded in our subconscious. Even when we think we treat everyone equally, pride ourselves on promoting equality, and call ourselves feminists, queer allies, and social justice activists, unconscious bias still pervades our minds and actions.

Bias is particularly injurious in the provision of health care. Even after differences in socioeconomic status are taken into account, Blacks and other minorities still receive lower quality of care than Whites. Innumerable studies in the American Journal of Public Health and Annals of Emergency Medicine show how bias can impact clinical decisions. Physicians tend to rate their Black patients as less intelligent, more likely to abuse drugs and be non-compliant with treatment, and less likely to desire an active lifestyle and have adequate social support. Minority children with accidental injuries are three times more likely to be reported for suspected child abuse than their White counterparts. Additionally, Black and Hispanic patients are two times less likely to receive pain medication in the emergency department than White patients.

James shared a similar account of being accused of seeking drugs and being denied pain medicine while seeking emergency treatment for a liver condition. His narrative is just one of many that I collected through the community-based research project.

This project grew out of a community need to address unconscious bias. During my first summer as a Community-Based Research Fellow through the Haas Center, I helped the Contra Costa Health Equity Team develop an unconscious bias training curriculum for health-care providers. The training has been piloted with over 500 providers and continues to raise awareness about the detrimental effects of provider bias. However, many participants have still expressed concerns about learning how to mitigate their bias in the clinical setting. I consulted with members of the Health Equity Team, and together we developed the next stage of research: interviewing patients and providers about their perceptions of unconscious bias in the health centers. This study seeks to center the voices of populations that have been historically marginalized and silenced. It will also identify concrete examples of insensitive behaviors in order to offer providers specific tools for reducing unconscious bias. I have already conducted 56 interviews with patients and providers, including the one with James, and have been qualitatively analyzing these transcripts over the last two quarters with the support of the Haas Center Public Service Scholars Program and my honors thesis advisors, Donald Barr and Jennifer Wolf. In the spring quarter, I will finish writing my honors thesis and deliver a presentation and report to Contra Costa Health Services with suggestions for improving the implicit bias training.

Community-based research has taught me the value of placing community needs at the forefront of identifying problems and enacting change. More specifically, this project with Contra Costa Health Services has given me the opportunity to explore unconscious bias in medicine, as well as my own unconscious bias. I am slowly becoming more aware of my own biases and more capable of stopping biased thoughts in their tracks. All the stereotypes we have learned can be unlearned once we recognize the ways in which we hold biases, foster dialogue about unconscious bias, and continue to acknowledge privilege and self-reflect on our actions and attitudes. Biases can be broken. With time and effort, injustices like those James has faced will become the exception rather than the norm.

You can find out more about your unconscious mind and take an Implicit Association Test (IAT) at Harvard’s Project Implicit.

Nikki Apana, ’20, studies Human Biology with a concentration in race, ethnicity, social class, and public health, and a minor in Spanish. Originally from Concord, California, Nikki has spent the last three summers in her hometown working as a Community-Based Research Fellow through Cardinal Quarter on issues of bias in the health-care system. At Stanford, Nikki serves as the lead Cardinal Service Peer Advisor, president of the Polynesian dance team Kaorihiva, and residential assistant in Branner Hall. Nikki has also worked as a SHAR(ED) volunteer throughout her Stanford career, was a Branner Hall Service Scholar, serves as a Cardinal Free Clinics Patient Health Advocate, and is a member of the Public Service Scholars Program.

Girls Run the World in Gorongosa National Park

By Eric Wilburn, MS ’18, MA ’18

Gabriela “Gaby” Curtiz grew up just down the road from Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique. The park is one of the most biodiverse places on Earth and is surrounded by more than 200,000 people who live on very limited resources. These neighboring communities struggle to make ends meet due to lack of employment. Many young women in these communities lack the opportunity to finish primary school because of societal expectations, household responsibilities, and a shortage of schools and teachers.

When Gaby was twelve years old, her primary school showed a National Geographic film about Gorongosa National Park, sparking her dream to work with animals in the park. Nine years later, Gaby was certified as the first female safari tourism guide in Gorongosa’s history.

I met Gaby last year on her first trip to the United States. She was visiting Boise State University, where she will begin her undergraduate studies this fall. Of course, service was a part of her trip! She gave a talk to a group of elementary school students about Gorongosa. It was amazing to see their eyes light up and their hands skyrocket to the ceiling with questions about her life in Gorongosa. She emphasized the importance of working with local communities in conservation efforts, and explained that providing livelihoods for local families was the key to sustainable nature conservation. Her example? Coffee.

Why coffee? Because there are hundreds of families like Gaby’s living on the flanks of Mount Gorongosa that need an alternative to unsustainable agricultural practices to feed their families. There is no need for farmers to cut down the forests to make room for non-native crops, as farmers can plant native hardwood saplings in between the rows of coffee to provide shade. Coffee gives these farmers a dependable income while helping restore the rainforests of Gorongosa.

I was thrilled to hear Gaby share her story, and was particularly excited when she chose coffee as her example. Having recently graduated from Stanford, I had just begun working with Gorongosa National Park to launch Gorongosa Coffee, a for-profit company that sells premium roasted coffee around the world and sends 100% of profits back to the park to support operating costs.

After her talk, Gaby and I were chatting about how Gorongosa Coffee wanted each of our roasted coffees to support a different initiative in the park. Gaby said that the most unique aspect of Gorongosa is that the park fundamentally believes that girls’ education is the key to both human development and nature conservation.

Inspired by Gaby, Gorongosa Coffee created a Girls Run the World coffee that sends 100% of profits to help over 20,000 girls in Gorongosa finish high school. The funds help build schools, provide high school scholarships, and connect girls with mentors through afterschool programs. We hope to demonstrate that when we give girls in Mozambique the confidence, capability, and opportunities to determine their own futures, we encourage more leaders like Gaby.

One of the defining aspects of our model that helps ensure our company has a positive impact is that the lone shareholder of Gorongosa Coffee is the trust that funds the park. In other words, Gorongosa Coffee is a social enterprise which keeps control of this community-based initiative within the community it serves.

Gaby graduated from high school in Gorongosa and will start at Boise State University in September, pursuing a degree in business tourism. Her goal is eventually to become the head of tourism for Gorongosa National Park.

Gaby and I come from very different backgrounds, but we share a commitment to serving the people, wildlife, and ecosystems of Gorongosa. We believe that the path forward for people and the planet is that every business thrives, not to fill the pockets of a few shareholders, but in service of an equitable and sustainable future for all.

I invite you to help us empower young women like Gaby from the communities of Gorongosa to break barriers and bring positive change to their communities. You may order our coffee at GorongosaCoffee.com.

Eric Wilburn, MS ’18, MA ’18, served in the Peace Corps in Mozambique before arriving at Stanford to pursue dual masters degrees in environmental engineering and public policy. During his time at Stanford, Eric was a Graduate Public Service Fellow and also coached the Stanford Triathlon Team. Recently, Eric has been helping to launch a company called Gorongosa Coffee that aims to benefit local communities, wildlife, and nature in Mozambique by supporting conservation, education, and economic development.

Engaging the Public in Advocacy for Survivors of Sexual Violence

By Elizabeth Kim, ’22

3, 2, 1. We were rolling.

It was only my third week as End Rape on Campus (EROC)’s campus data fellow, and here I was, speaking to hundreds of people as I explained concepts that I had only grasped the nuances of a week earlier. I was aided, of course, by my boss: EROC Policy Director Ever Hanna, an attorney whose detailed knowledge of government, law, and sexual violence advocacy never ceased to awe me.

In this Facebook livestream, however, we were sitting side by side, co-hosting an informative Q&A on topics that ranged from affirmative consent to the Clery Act, a law that aims to provide transparency about campus crime policy and statistics. Though I’d spent many hours anticipating and rehearsing the answers to questions tweeted to us from all over the country, I was terrified of saying the wrong thing. Could my new understanding of this incredibly complex issue fail me, forever tarnishing the reputation of this organization that I already loved so much?

My primary project during the summer with EROC was helping establish an accessible, accurate, self-sustaining School Accountability Map, with the goal to make every U.S. college and university’s sexual assault policies and history accessible to the average college student. Because every school in the U.S. interprets Title IX differently, and few make that information accessible to students, the map will improve transparency and put power in the hands of student survivors. It was my job to develop and launch the Map Volunteer Campaign—to recruit, instruct, and vet the research of the volunteers who would collect information on each school. This livestream was meant for these volunteers, many of whom identify as survivors themselves, as they navigated the gargantuan task of researching and processing their school’s Title IX policies.

The goal of the livestream Q&A was not only to inform our volunteers, but to excite and motivate them about the work ahead. We wanted to empower volunteers with answers to their questions, but also show them that they already possessed the intelligence, courage, and persistence needed to educate their own communities about their school’s history with sexual violence.

Fun, informative, and relatable. These were the words I chanted in my head as our communications director counted down the seconds to us rolling, but soon I forgot about them. I rattled off different definitions, fielded a viewer question about due process, and chimed in on Ever’s explanation of how federal agencies can mandate different interpretations of Title IX. I felt myself falling into the rhythm that I so often enjoyed while watching talk show hosts vibe with guests they knew well.

I came out of the livestream that day not only with a more profound sense of confidence, but also an important realization: fully understanding something means you can explain it to another person. And an explanation requires a willingness to engage and put yourself out there.

This is the sort of heightened confidence I draw from as a student seeking to raise greater awareness about Stanford’s own culture of sexual violence. Whether I’m writing an Op-Ed or participating in an awareness campaign, I’ve realized that there are many ways to engage the community—each as important as the next.

Originally from Boston, MA, Elizabeth Kim, ’22, majors in economics at Stanford. In addition to her service through the Cardinal Quarter program as End Rape on Campus’s data fellow during the summer of 2019, Elizabeth serves as a French language conversation partner at the Stanford Center for Teaching and Learning and chairs philanthropy and alumni relations for Sigma Psi Zeta Sorority.

The Value and Validity of Nontraditional Education Paths

By Tess Stewart, ’21

Last summer, I had the pleasure of working as an admissions and recruitment intern at Year Up, an education nonprofit that aims to take young adults ages 18 to 24 from minimum-wage jobs to well-paying careers in just one year. Year Up’s program is split into two phases. The first phase, learning and development, focuses on teaching these young professionals the necessary skills to succeed in the modern workforce. During the next six months, students are placed at an internship to gain real-world working experience.

As part of the admissions and recruitment team, I helped build the next class of Year Up students. By far, my favorite part of the job was conducting admissions interviews. I would spend about an hour talking individually with young adults from all walks of life about their experiences, passions, and goals. I was exposed to such a breadth of wonderful people who were motivated to kickstart their professional careers.

Additionally, this summer was especially unique because it opened my eyes to the variety of paths to success that exist. I am extremely lucky to attend an institution such as Stanford, but my internship helped me realize that getting a college degree is by no means the only way to achieve one’s goals. Through my work at Year Up, I was able to work with incredibly smart young adults who were in the process of following an untraditional path toward their goals. Whether deciding to restart their education after having their second child or deciding that a string of minimum-wage jobs just was not cutting it anymore, these young adults approached Year Up with the passion and drive to reach their dream job.

As an intern, I was able to witness the immense impact Year Up has on the lives of its students. Not only does Year Up provide students with a stable support system, career advice, and tangible tools to use in the workforce, but this organization also teaches students to have confidence in themselves and their value in the professional world. Furthermore, it forced me to reflect on my own time at Stanford. I began thinking critically about my own learning, questioning how successfully I was utilizing my time at Stanford to reach my goals. Working at Year Up greatly broadened my view about what it means to be a young professional and how we can support individuals who may have untraditional paths, so that, regardless of background, students can reach their full potential.

Tess Stewart, ’21, is originally from Los Angeles, CA, and studies symbolic systems at Stanford. In the summer of 2019, Tess completed a Cardinal Quarter as part of the admissions and recruitment team at Year Up, a year-long program that supports young professionals in pursuit of meaningful and sustainable careers.

Starting Small for Big Change: Edith Asibey, MA ’97, on Tiny Habits

By Erika DePalatis, ’19

“How do we convince people to get involved, to take action in worthwhile causes?”

This is the question that motivates Edith Asibey, MA ’97. Born in Italy and raised in Paraguay, Asibey studied biology and education at the University of São Paulo in Brazil, and later pursued a MA in media studies at Stanford University. Through these experiences, Asibey quickly discovered a passion for social justice and a desire to use her voice to uplift the voices of others.

Upon graduating from Stanford, Asibey began working for nonprofits and humanitarian groups in Latin America and around the world. As she rose to leadership roles, she would encounter the same challenge over and over again: while individuals might be quick to voice support for a cause, often the same audience would find it difficult to take practical actions to advance the cause.

How could nonprofits and humanitarian organizations move their audiences from good intentions to meaningful action, and sustain their involvement over time?

In pursuit of answers, Asibey recalled the work of BJ Fogg, MA ’95, PhD ’97, a fellow graduate student she had met during her time at Stanford. Fogg, a behavioral scientist leading the Stanford Behavior Design Lab, had designed a method for behavior change called Tiny Habits®. This method allows individuals to change a behavior in the long term by tapping into the power of their environment and taking baby steps.

“Upon starting to practice Tiny Habits [personally], I saw positive changes immediately,” Asibey recalls. “For example, I crafted this Tiny Habit: After I pick up my mobile for the first time in the morning, I will text a good morning message to my mother. Since I started practicing this habit, I have carried it out almost infallibly, every day for over a year and a half. What’s more, if I don’t do it early enough, my mom texts me first. So, she, too, developed the habit – an unexpected result!”

In Fogg’s method and foundational models of Tiny Habits, Asibey saw a tool to help boost action and generosity. “If we can learn how to crack the code to develop our own healthy habits, why couldn’t we use it to act more generously towards others?” Asibey wondered. After becoming a Certified Tiny Habits Coach, Asibey started a free, weeklong online program to help individuals develop their own Generous Habits. Through her firm Asibey Consulting, she also uses principles of behavioral science to help mission-driven organizations successfully take audiences from intention to action.

Asibey shares Tiny Habits with others as a way to “build motivation, confidence, and hope.” In response to the uncertainty many are feeling during the COVID-19 pandemic, Asibey writes:

I am heartened by the worldwide demonstrations of people caring and mobilizing to help one another during this time. To students, especially those who have returned home or have settled somewhere safe, I encourage you to consider these three suggestions:

- Practice Tiny Habits for Generosity. While the method calls for each of us to design our own Tiny Habits, below, I share two ideas for practicing Tiny Habits for Generosity that I hope will bring positivity to your relationships with classmates, family and friends. Use these recipes “as-is,” or as inspiration to craft your own!

- After I pick up my mobile phone for the first time in the day, I will text a loved one to check on them.

- After I come across the first person I don’t know, I will look at them and say ‘hi’ with a smile.

- Check on classmates and friends whose families are abroad or who are unable to travel home. Speaking from my own experience as an international student at Stanford, I vividly remember how hard it was to be so far away from my family and friends back home. Something that made a huge difference in making me less homesick was to have my American classmates, people like Gina Baleria, MA ’97, take the time to get to know me, introduce me to family and friends, and show me how to properly order at a diner! In these complicated times, be sure to contact your fellow students who may not be in a position to return home and see how they are doing. Their families might also be in countries heavily affected by COVID-19.

- Offer help in your community. In the true spirit of Cardinal Service, your help might be needed back home or in the community where you are temporarily settled. Of course, your health and safety must always come first. Be sure to abide by all local and national public health orders while engaging in service. But if you have the means, see what you can do to help those who are most vulnerable. Here is a simple idea from Becky Wass in the UK: a #ViralKindness card to help your neighbors while staying safe. For more daily inspiration on how to help create a brighter world, subscribe to Giving Tuesday’s “Daily Generosity Alert.”

Visit the Haas Center for Public Service’s Community Care page to discover more ideas of how to serve your community while keeping yourself and others safe during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Erika DePalatis, ’19, serves as the Communications Coordinator at the Haas Center for Public Service. Prior to her work at Haas, Erika studied English and Italian at Stanford and worked as an oral communications tutor at the Hume Center for Writing and Speaking. Her role allows her to elevate student stories of service and connect Stanford students with service opportunities.