Category: Cardinal Quarter

Revisiting Milwaukee: Learning About My Hometown Through Service

By Elyse Cornwall, ’22

The first time I drove to Moody Park, I suppressed my nerves about driving into an area known for reckless driving. I reminded myself that these feelings came from racist assumptions about a community I had never meaningfully interacted with. Still, I stopped at green lights as oncoming cars ran the red, and rushed down main streets to keep other cars from skirting past me. Thus, I arrived at Moody Park feeling simultaneously afraid and embarrassed, and that was when the youth participants arrived. My primary responsibilities were event planning and coordinating with other volunteers, but I realized that my work behind the scenes could not be effective until I immersed myself in the community I served. When I ate meals, played games, and shared stories at Moody Park, a new side of my service experience emerged.

My weekly discussions with youth living near Moody Park covered topics like drugs and alcohol, police relations, and reckless driving. The group’s familiarity with dangerous situations seemed to contradict their charisma and friendliness. I helped host the Zeidler Center’s listening circle events, which allowed youth and police officers from the area to talk with each other in small groups. The youth took turns responding to prompts such as, “Describe an experience you have had with a police officer,” sharing their experiences rather than debating or convincing anyone. The Zeidler Center hosts listening circles like these throughout the Greater Milwaukee Area, featuring topics like political polarization, race relations, and education. These events are based on the organization’s belief that open, respectful dialogue promotes positive change. I watched as the listening circles at Moody Park shifted from short responses to candid conversation. By the end of the discussions, youth and officers were sharing accounts of their days and stories of hardship, relating to one another on a personal level.

As an outsider in this community, I felt hesitant to expand beyond my role as a staff member, but eventually gave in with the encouragement of the youth and other staff. I shared my own experiences, admitted the gaps in my knowledge of Milwaukee, and put myself in a position to learn from the youth I had aimed to serve. Not only did I feel more connected to a community that I hadn’t interacted with before, but I also felt a stronger obligation towards my city. I found that my view of civic duty and participation changed once I got to know the people with whom I was sharing a community.

By the end of the summer, I started to see my service experience in connection to my parents’ work in Milwaukee as public servants. Usually, I thought of my parents as lawyers who happened to work for the state and county. Though they had expressed pride in serving those who relied upon public legal assistance, I never thought of their occupations as reflections of their character. As a court commissioner, my father has the opportunity to combat the racial bias that targets people with his racial identity in most courtrooms. Like my father, the staff and volunteers at the Zeidler Center prioritize listening to and learning from the communities they serve.

I am glad to have developed this new civic understanding in the context of Milwaukee, through the service I have done. When I returned to Stanford in the fall, I brought with me a willingness not only to serve, but also to know the people within my community who are most targeted and misrepresented.

Elyse Cornwall, ’22, studies computer science at Stanford. Originally from Milwaukee, WI, Elyse completed a Cardinal Quarter in her hometown the summer after her freshman year, working to support the Zeidler Center, an organization that fosters civil dialogue across perspectives. At Stanford, Elyse is a CS106A section leader; a team leader for Ideas Out Loud, Stanford’s TEDx club; and a member of the Delta Delta Delta Sorority.

Flying Solo at the Santa Lucia Conservancy

By Max Klotz, ’20

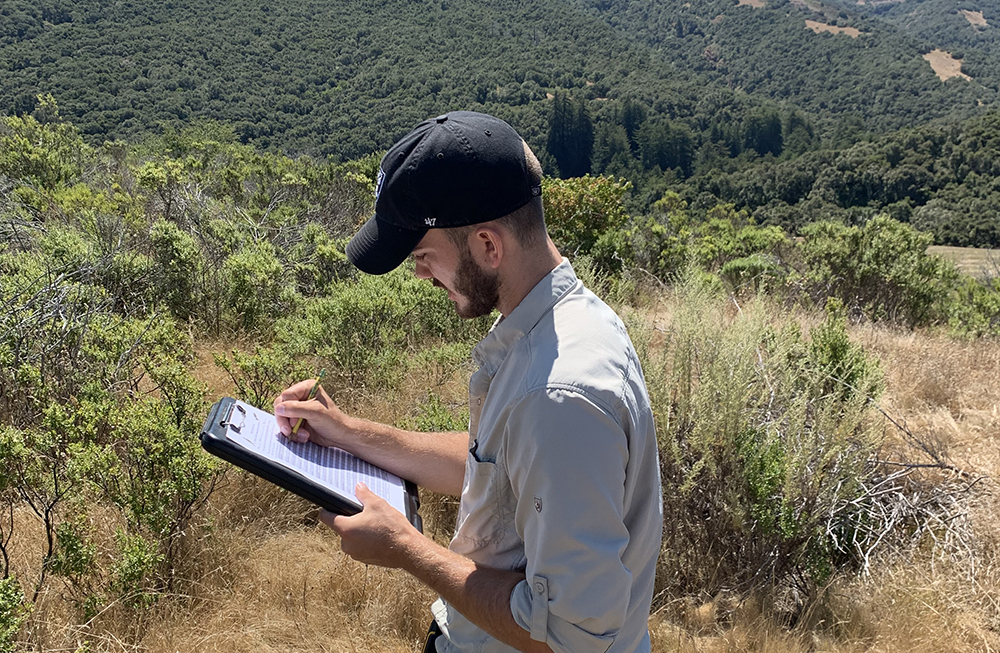

When I made it to the trailhead, Hall’s Ridge was still blanketed in mist. I couldn’t see 15 feet from me, let alone the views down into the valleys on either side of the ridge. I used the delay to organize my photos and make sure I knew the location of each photo point, places with distinctive landmarks that could provide a record for evaluating vegetation changes over time.

The morning mist quickly gave way to sun as, seemingly in minutes, the fog layer around me burned off to reveal views all the way to Monterey Bay. Now having the visibility necessary to capture my photographs, I set off on the trail. I spent the rest of the day hiking and taking pictures, not just of my photo points, but also of the hawks and vultures that circled by the trail.

My project at the Santa Lucia Conservancy in Carmel consisted of selecting and replicating historical photographs of the Santa Lucia Preserve to show the land’s changes over time as part of broader ecological conservation efforts. The process for obtaining repeat photographs of each historical picture was intricate. First, I had to carefully select historical photographs that featured distinctive landmarks in the preserve. Then I worked with my supervisor to identify the approximate locations of each historic photo point and map them using waypoints on the MapItFast software. Finding the exact location for each historical photograph and taking current pictures with the same framing were the final and most challenging steps. I had been struck by the beauty of some of the historical photographs on Hall’s Ridge, so I was excited to explore the area. Early on in my internship at the Santa Lucia Conservancy, I had mostly explored the preserve with other employees, but as my project progressed, I came to enjoy the meditative nature of the days I spent on my own. I set out in a company truck with my water, lunch, camera, and stack of historical photographs. Several weeks into my project, I began to make my way around the different photo locations on the preserve to capture what those photo points look like now. In the process of driving and hiking from place to place in search of historic photo locations, I started to become familiar with the land and its intricacies.

As I looked at my photographs at the end of the summer, I realized the project had shown intriguing results. There had been dramatic changes in some areas of the preserve and a dramatic lack of change in others. Through photography, I was able to track brush encroachment on grasslands, lands recovering from fire treatment, and other broad changes over the course of decades.

This hands-on Cardinal Quarter experience has given me an understanding of the power of combining ecological studies with creative work, as well as a desire to continue to use these tools throughout my career.

Originally from Stanford, CA, Max Klotz, ’20, studies human biology with a concentration in environmental studies. Max completed a Cardinal Quarter during the summer of 2019 with the Santa Lucia Conservancy in Carmel, CA. In addition to engaging in a range of hands-on conservation activities, he helped develop a project to reproduce historical photographs of the Santa Lucia Preserve in order to document environmental change over time. View his “Repeat Photography” project on the Santa Lucia Conservancy website.

Policymaking by Empathy: Interning at the State Department

By June Lee, ’21

It’s 8:10am when I walk into the office, my blouse lightly dampened by my walk under the merciless Washington, D.C. sun. As I head to my cubicle, I hear snatches of conversations on the humanitarian crisis in Yemen and the current status of peacekeeping in Mali. I can’t help but feel a secret thrill to be working alongside individuals on issues I’d only ever read about and studied in classes.

Interning at the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Conflict Stabilization Operations was, academically, one of the most enriching experiences I’ve had. Through weekly meetings, I gained exposure to the incredible breadth of concerns incorporated into the United States’ conflict stabilization efforts, from the role of women in peace processes, to the importance of intra-group cohesion in negotiations, to the efficacy of interventions by nonprofits and other third parties. No matter what project I was working on, it was fascinating to realize that here, my efforts could have a direct application for policy. Translating an article evaluating violence reduction in Colombia could directly inform the bureau’s engagement with partner organizations on the ground. Similarly, developing a digital framework on Excel depicting election violence indicators could help the bureau allocate funding and resources quickly to mitigate the risks of political violence. Over time, I also gained familiarity with the inter-agency process and overlapping departmental structures responsible for developing and implementing U.S. foreign policy.

Yet the most valuable thing I learned from my internship was the incredible depth of empathy it takes to work as a public servant in the State Department. The individuals I encountered worked on projects that directly affected the welfare of communities in countries emerging from conflict, and they were constantly thinking about the communities they were seeking to support. This mindset translated to all aspects of their work. My main supervisor related how, while serving as a foreign service officer in New Delhi, he would often bike to work with a camera, and offer to take pictures of people on the street. Their surprise and joy upon receiving a picture of themselves led to his receiving a flurry of texts and blessings every holiday. Another director, frustrated with the United States’ failure to address the humanitarian crisis in Syria, was motivated to resign and work for a nonprofit focused on human rights advocacy for Syrians and other refugees. And, during my daily commute, another officer explained how he had worked in Afghanistan for 18 years, an experience he spoke of with a hint of sadness but also admiration for the resilience of the Afghan people.

Since my internship, I’ve been determined to embrace this mindset. As a director of Stanford in Government and a peer advisor in international relations, I’ve sought to encourage more students to pursue careers in policy and public service. And, while working on my senior thesis, I am committed to developing a research paper that can be beneficial to policymakers and useful in advancing the United States’ efforts in conflict resolution.

Originally from Sunnyvale, CA, June Lee, ’21, studies international relations at Stanford. In addition to completing a Cardinal Quarter summer fellowship with the State Department’s Bureau of Conflict Stabilization Operations in the summer of 2019, June serves as the director of diversity and outreach of Stanford in Government and as a peer advisor for the international relations department. June is also an incoming honors student with the Freeman Spogli Institute’s Center for International Security and Cooperation.

Unequal Treatment: Exploring Unconscious Bias in Health Care

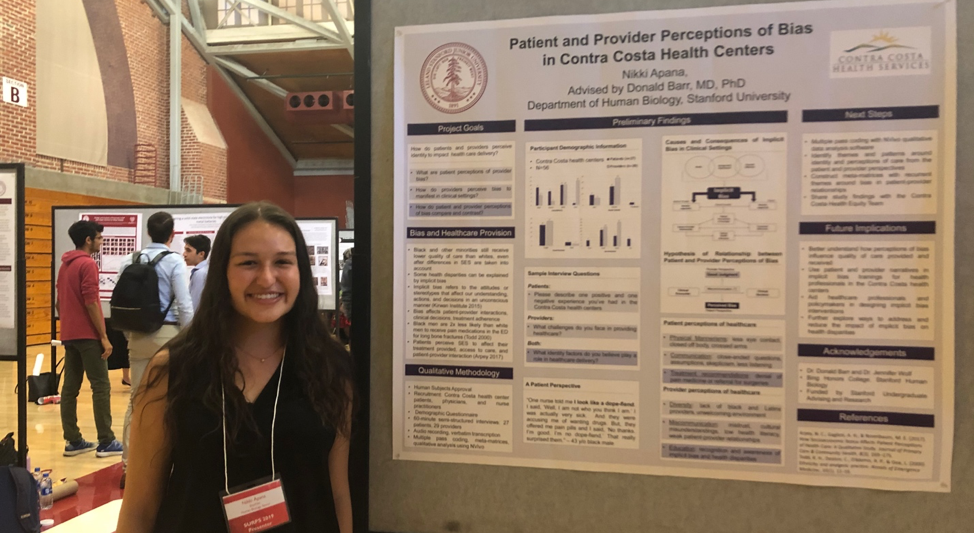

By Nikki Apana, ’20

“One nurse told me I look like a dope fiend. I said, ‘Well, I am not who you think I am.’ I was actually very sick.… And they were accusing me of wanting drugs.” – James (pseudonym), 43-year-old Black male

James is a participant in the community-based research project I have been conducting over the past three summers. I have been collaborating with Contra Costa Health Services, the public health system in my hometown, to find ways to address unconscious bias in patient care. Unconscious bias refers to the stereotypes we internalize that affect our behavior, judgments, and actions without our conscious awareness. And what is so pernicious about unconscious bias is that everyone has it, yet few realize it.

Unconscious bias covertly plays out in our everyday lives. As described in Howard Ross’s Everyday Bias, NBA referees call more fouls against Black players than White players, famous Black actor Danny Glover reported struggling to hail a New York City cab after dark, and job applicants with “Black” names are less likely to receive a callback than applicants with “White” names. Bias extends beyond race to gender, sexuality, socioeconomic status, age, and weight. It surrounds us every day and it is embedded in our subconscious. Even when we think we treat everyone equally, pride ourselves on promoting equality, and call ourselves feminists, queer allies, and social justice activists, unconscious bias still pervades our minds and actions.

Bias is particularly injurious in the provision of health care. Even after differences in socioeconomic status are taken into account, Blacks and other minorities still receive lower quality of care than Whites. Innumerable studies in the American Journal of Public Health and Annals of Emergency Medicine show how bias can impact clinical decisions. Physicians tend to rate their Black patients as less intelligent, more likely to abuse drugs and be non-compliant with treatment, and less likely to desire an active lifestyle and have adequate social support. Minority children with accidental injuries are three times more likely to be reported for suspected child abuse than their White counterparts. Additionally, Black and Hispanic patients are two times less likely to receive pain medication in the emergency department than White patients.

James shared a similar account of being accused of seeking drugs and being denied pain medicine while seeking emergency treatment for a liver condition. His narrative is just one of many that I collected through the community-based research project.

This project grew out of a community need to address unconscious bias. During my first summer as a Community-Based Research Fellow through the Haas Center, I helped the Contra Costa Health Equity Team develop an unconscious bias training curriculum for health-care providers. The training has been piloted with over 500 providers and continues to raise awareness about the detrimental effects of provider bias. However, many participants have still expressed concerns about learning how to mitigate their bias in the clinical setting. I consulted with members of the Health Equity Team, and together we developed the next stage of research: interviewing patients and providers about their perceptions of unconscious bias in the health centers. This study seeks to center the voices of populations that have been historically marginalized and silenced. It will also identify concrete examples of insensitive behaviors in order to offer providers specific tools for reducing unconscious bias. I have already conducted 56 interviews with patients and providers, including the one with James, and have been qualitatively analyzing these transcripts over the last two quarters with the support of the Haas Center Public Service Scholars Program and my honors thesis advisors, Donald Barr and Jennifer Wolf. In the spring quarter, I will finish writing my honors thesis and deliver a presentation and report to Contra Costa Health Services with suggestions for improving the implicit bias training.

Community-based research has taught me the value of placing community needs at the forefront of identifying problems and enacting change. More specifically, this project with Contra Costa Health Services has given me the opportunity to explore unconscious bias in medicine, as well as my own unconscious bias. I am slowly becoming more aware of my own biases and more capable of stopping biased thoughts in their tracks. All the stereotypes we have learned can be unlearned once we recognize the ways in which we hold biases, foster dialogue about unconscious bias, and continue to acknowledge privilege and self-reflect on our actions and attitudes. Biases can be broken. With time and effort, injustices like those James has faced will become the exception rather than the norm.

You can find out more about your unconscious mind and take an Implicit Association Test (IAT) at Harvard’s Project Implicit.

Nikki Apana, ’20, studies Human Biology with a concentration in race, ethnicity, social class, and public health, and a minor in Spanish. Originally from Concord, California, Nikki has spent the last three summers in her hometown working as a Community-Based Research Fellow through Cardinal Quarter on issues of bias in the health-care system. At Stanford, Nikki serves as the lead Cardinal Service Peer Advisor, president of the Polynesian dance team Kaorihiva, and residential assistant in Branner Hall. Nikki has also worked as a SHAR(ED) volunteer throughout her Stanford career, was a Branner Hall Service Scholar, serves as a Cardinal Free Clinics Patient Health Advocate, and is a member of the Public Service Scholars Program.

Engaging the Public in Advocacy for Survivors of Sexual Violence

By Elizabeth Kim, ’22

3, 2, 1. We were rolling.

It was only my third week as End Rape on Campus (EROC)’s campus data fellow, and here I was, speaking to hundreds of people as I explained concepts that I had only grasped the nuances of a week earlier. I was aided, of course, by my boss: EROC Policy Director Ever Hanna, an attorney whose detailed knowledge of government, law, and sexual violence advocacy never ceased to awe me.

In this Facebook livestream, however, we were sitting side by side, co-hosting an informative Q&A on topics that ranged from affirmative consent to the Clery Act, a law that aims to provide transparency about campus crime policy and statistics. Though I’d spent many hours anticipating and rehearsing the answers to questions tweeted to us from all over the country, I was terrified of saying the wrong thing. Could my new understanding of this incredibly complex issue fail me, forever tarnishing the reputation of this organization that I already loved so much?

My primary project during the summer with EROC was helping establish an accessible, accurate, self-sustaining School Accountability Map, with the goal to make every U.S. college and university’s sexual assault policies and history accessible to the average college student. Because every school in the U.S. interprets Title IX differently, and few make that information accessible to students, the map will improve transparency and put power in the hands of student survivors. It was my job to develop and launch the Map Volunteer Campaign—to recruit, instruct, and vet the research of the volunteers who would collect information on each school. This livestream was meant for these volunteers, many of whom identify as survivors themselves, as they navigated the gargantuan task of researching and processing their school’s Title IX policies.

The goal of the livestream Q&A was not only to inform our volunteers, but to excite and motivate them about the work ahead. We wanted to empower volunteers with answers to their questions, but also show them that they already possessed the intelligence, courage, and persistence needed to educate their own communities about their school’s history with sexual violence.

Fun, informative, and relatable. These were the words I chanted in my head as our communications director counted down the seconds to us rolling, but soon I forgot about them. I rattled off different definitions, fielded a viewer question about due process, and chimed in on Ever’s explanation of how federal agencies can mandate different interpretations of Title IX. I felt myself falling into the rhythm that I so often enjoyed while watching talk show hosts vibe with guests they knew well.

I came out of the livestream that day not only with a more profound sense of confidence, but also an important realization: fully understanding something means you can explain it to another person. And an explanation requires a willingness to engage and put yourself out there.

This is the sort of heightened confidence I draw from as a student seeking to raise greater awareness about Stanford’s own culture of sexual violence. Whether I’m writing an Op-Ed or participating in an awareness campaign, I’ve realized that there are many ways to engage the community—each as important as the next.

Originally from Boston, MA, Elizabeth Kim, ’22, majors in economics at Stanford. In addition to her service through the Cardinal Quarter program as End Rape on Campus’s data fellow during the summer of 2019, Elizabeth serves as a French language conversation partner at the Stanford Center for Teaching and Learning and chairs philanthropy and alumni relations for Sigma Psi Zeta Sorority.

The Value and Validity of Nontraditional Education Paths

By Tess Stewart, ’21

Last summer, I had the pleasure of working as an admissions and recruitment intern at Year Up, an education nonprofit that aims to take young adults ages 18 to 24 from minimum-wage jobs to well-paying careers in just one year. Year Up’s program is split into two phases. The first phase, learning and development, focuses on teaching these young professionals the necessary skills to succeed in the modern workforce. During the next six months, students are placed at an internship to gain real-world working experience.

As part of the admissions and recruitment team, I helped build the next class of Year Up students. By far, my favorite part of the job was conducting admissions interviews. I would spend about an hour talking individually with young adults from all walks of life about their experiences, passions, and goals. I was exposed to such a breadth of wonderful people who were motivated to kickstart their professional careers.

Additionally, this summer was especially unique because it opened my eyes to the variety of paths to success that exist. I am extremely lucky to attend an institution such as Stanford, but my internship helped me realize that getting a college degree is by no means the only way to achieve one’s goals. Through my work at Year Up, I was able to work with incredibly smart young adults who were in the process of following an untraditional path toward their goals. Whether deciding to restart their education after having their second child or deciding that a string of minimum-wage jobs just was not cutting it anymore, these young adults approached Year Up with the passion and drive to reach their dream job.

As an intern, I was able to witness the immense impact Year Up has on the lives of its students. Not only does Year Up provide students with a stable support system, career advice, and tangible tools to use in the workforce, but this organization also teaches students to have confidence in themselves and their value in the professional world. Furthermore, it forced me to reflect on my own time at Stanford. I began thinking critically about my own learning, questioning how successfully I was utilizing my time at Stanford to reach my goals. Working at Year Up greatly broadened my view about what it means to be a young professional and how we can support individuals who may have untraditional paths, so that, regardless of background, students can reach their full potential.

Tess Stewart, ’21, is originally from Los Angeles, CA, and studies symbolic systems at Stanford. In the summer of 2019, Tess completed a Cardinal Quarter as part of the admissions and recruitment team at Year Up, a year-long program that supports young professionals in pursuit of meaningful and sustainable careers.

Global Engagement: Engineering Solutions for Sustainability

By Adam Nayak, ’22

Ever since I was little, I have been fascinated with water. I grew up four blocks from Johnson Creek, a local stream in southeast Portland, Oregon. My mom took me down to the park to play in the water, letting the currents wrap around my legs as I searched for tadpoles and capered with dragonflies.

Each month, my family would wake up early in the morning to work with our local watershed council, removing invasive species, planting native species, and picking up trash around the stream.

It was here that my younger sister and I learned about the great salmon migration. I remember being fascinated with the fish: their perseverance, determination, and tenacity, traversing upstream to their birthplace to continue their lineage. As a boy, I was always searching for salmon, but as an urban stream, Johnson Creek faced serious water-quality challenges due to a history of pollution, and I was never able to find any fish.

As I grew older, I developed an interest in the science behind water treatment and ecological systems, looking for solutions to problems of contaminated stormwater and habitat loss. Volunteering with the Johnson Creek Watershed Council was one of my most rewarding experiences, instilling in me a value for public service and community engagement that has grown with me at Stanford.

Through my involvement in Engineers for a Sustainable World (ESW), a Cardinal Commitment student organization, I have been able to pair my interest in environmental conservation with engineering practice. In particular, I worked on a small team of students during a two-quarter Cardinal Course to design and prototype sustainable infrastructure solutions in Chavín de Huántar, Perú, an archaeological site in the Andes Mountains. Through the Cardinal Quarter program, I traveled to Perú with my team this past summer to implement the project and promote cultural conservation.

Our green roofs and modular tensile structures were designed as a new approach to flood mitigation in a rural setting, with a focus on aesthetic integration of roofing structures at a culturally significant site. This opportunity not only strengthened my Spanish language and communication skills, it allowed me to collaborate with engineers and community members, as well as to learn about engineering practices in the context of a different culture and setting.

Service is powerful to me because it establishes a sense of community and belonging. As a student who is passionate about equity and inclusion, I hope to work on sustainability projects in diverse communities worldwide. The experience in Perú has enhanced my ability to collaborate on a team that spans cultural backgrounds and has reaffirmed my passion for public service projects.

Now as a sophomore, I co-lead international ESW projects focused on sustainable engineering and equitable development. They have brought me back to the theme of water, leading a project with community partners in Ghana focused on organic waste mitigation and water treatment through biochar production for carbon filtration.

For me, service involves building relationships and working collaboratively, whether internationally with an organization like el Ministerio del Cultura de Perú, or locally with the Johnson Creek Watershed Council. Both experiences involved a long-term commitment to addressing community needs. From these experiences, I have come to focus on promoting equitable access to resources for all communities, regardless of background. Looking forward, I hope to continue my work in sustainable development as an environmental engineer, focusing on clean water and equity practices in the public sector.

Adam Nayak, ’22, studies civil and environmental engineering. Originally from Portland, Oregon, Adam’s childhood interest in environmental sustainability has led him to pursue a Cardinal Quarter in Perú, enroll in Cardinal Courses, make a Cardinal Commitment with Engineers for a Sustainable World, and serve as a Cardinal Service peer advisor. Adam has also been involved in the Multiracial Identified Community at Stanford; Stanford Strategies for Ecology Education, Diversity, and Sustainability; Students for the Liberation of All People; and Students for a Sustainable Stanford.

Listen Deeply and Act Strategically: Organizing for More Equitable Education in Colorado

By Tavia Teitler, ’21

I could see the majestic Colorado mountains in my rearview mirror and feel butterflies in my stomach as I pulled into the parking lot of Sister Carmen Community Center. It was my first day of work at Engaged Latino Parents Advancing Student Outcomes (ELPASO), and it only took about 10 minutes of the weekly Monday morning staff meeting for me to realize that I would be working for a truly incredible organization.

The ELPASO community organizers and school-readiness coordinators introduced themselves to me and immediately launched into a discussion about ways to effectively engage with their community in the current climate of fear about immigration. ELPASO’s then executive director, Tere Garcia, then spoke passionately about her new idea for a teddy bear clinic that could help raise awareness about the importance of preventative medical care. As I listened, I was blown away by the passion, energy, and power in the room. My sense of awe and inspiration only grew throughout the summer as I became more familiar with the women of ELPASO and the work they do.

I am majoring in comparative studies in race and ethnicity with a concentration in inequality in education, so a lot of my time at Stanford has been spent learning about theories of education inequity. However, I lacked intimate firsthand knowledge of what people were doing in their communities to tackle these issues. In other words, I didn’t know what many of these concepts and theories looked like on the ground.

ELPASO is a community organization based in Boulder, Colorado, that works to help close the opportunity and achievement gap between White and Latinx students in the area through effective parent engagement. By learning about ELPASO’s parent training and parent advocacy groups, I came to appreciate the power of informed, organized parents, and gained a deeper understanding of all of the factors that go into fighting for more equitable education. The theories I had learned about in the classroom came to life for me as I tagged along as the coordinators went door to door to recruit parents for their training program and listened as parents described their experiences raising their children in this country. I attended meetings with the parent advocacy group to ask school district officials to revise their translator policies and hire bilingual school secretaries. I also took notes as the women held a meeting with the director of the local free clinic to voice concerns about how they and the parents they work with were being treated. Later in the summer, I helped prepare materials for a workshop at a local trailer park on how to fill out money orders properly after the residents were robbed of a month’s rent by their landlord.

I was inspired by the organizers’ and coordinators’ ability to respond to more immediate needs in their community while still maintaining focus on their long-term mission. I learned lessons in the field from the women of ELPASO that both challenged and informed the lessons I’ve learned in the classroom. Most importantly, the women of ELPASO showed me what it means to listen deeply and act strategically. I know I will bring this knowledge back to the classroom, and out into the world after graduation.

This summer helped me realize that community organizing and nonprofit work, especially in relation to issues of education access and equity, is the kind of work I want to do in the future. Though I still need to spend time reflecting on my place as a White Stanford student in organizations that serve historically marginalized communities, I now know that I am committed to learning, just as I learned from my co-workers at ELPASO.

Originally from Carbondale, Colorado, Tavia Teitler, ’21, is majoring in comparative studies in race and ethnicity and psychology. Her interest in education equity led her to return to her home state for a Cardinal Quarter fellowship with Engaged Latino Parents Advancing Student Outcomes (ELPASO) during the summer of 2019. Tavia also serves as a community engaged learning coordinator at the Haas Center for Public Service and as co-chair of Ballet Folklórico de Stanford, a Mexican folk dance group on campus.

Our Islands, Our Stories: Oral History and Community-Building in Southeast Alaska

By Regina Kong, ’22

We were inside Taiga’s fishing boat, docked at the back of the cove. I remember taking a deep breath before setting the voice recorder down on the wooden table. The boat swayed side to side with the afternoon currents. Behind Taiga, I could see thickets of salmonberries and wild blueberries. According to the locals, the dense vegetation sheltered bears that roamed the island. I began the interview by asking Taiga about his childhood, and from there, I followed him as he spoke about everything from commercial fishing to ecology to fatherhood. To this day, everything about that experience and that summer feels entirely surreal.

Taiga was one of 15 people I interviewed for an oral history project I conducted through an internship with the Inian Islands Institute, a nonprofit experiential field school in Southeast Alaska that engages students in climate advocacy and sustainability. I found Inian as if by fate. When I reached out to Inian’s director, Zach Brown, PhD ’14, a few months prior to the summer of 2019, I learned that they had wanted to do an oral history project for a while, but had never had the capacity to do so.

“Do you think you would like to do this?” Zach asked me during one of our initial phone calls.

“Absolutely,” I said.

From a young age, I have always loved stories, especially those involving multiple generations and cultures. When I began thinking about interning with Inian, I was halfway through my freshman year and already thinking deeply about what a true education meant and what forms of wisdom could be attained outside of the traditional classroom—questions that I discovered resonated with Inian’s own mission.

And that was how, not even a week after the last day of school, I found myself in the breathtaking Southeast Alaskan wilderness, surrounded by endless swathes of forest and ocean. For the rest of the summer, I traveled by boat or seaplane to various communities, collecting stories surrounding the island’s homestead, fondly known by local fishermen as the “Hobbit Hole.” My goal was to preserve important community narratives containing such rich anthropological, ecological, and cultural histories; in the process of doing so, I realized that I was also preserving something much deeper.

Oral histories are a methodology for recording and preserving information not found in written records. Because they are shaped by the contours of an individual’s experience and reflections, they allow for the unearthing of rich and often unexpected stories. While these interviews proved emotionally intense, they also taught me how to listen deeply, how to be fully present. I heard incredible stories and met the wisest and most generous people. Strangers like Taiga shared their homes and lives with me, and I will always be grateful for that. From the changing climate in Southeast Alaska to the area’s geologic history to diverse definitions of home, I found myself continually learning more about this unique community as well as discovering a greater human narrative of love, endurance, and connection.

I know this summer will continue to shape who I am for the rest of my life, and I hope to take these stories and gleams of wisdom with me wherever I am in the world. To Taiga and everyone else who made this experience as special as it was and continues to be, thank you from the bottom of my heart.

Regina Kong, ’22, is from Berkeley, California, and is currently studying comparative literature and art practice at Stanford. She spent the summer of 2019 gathering oral histories from locals in Southeast Alaska as part of the Donald Kennedy Summer Projects Cardinal Quarter fellowship with the Inian Islands Institute. At Stanford, Regina serves as a producer for the Stanford Storytelling Project and works as a student tour guide.

When Home is a Region: Working Towards an Inclusive Bay Area

By Nani Friedman, ’20

In my second week as an intern at Enterprise Community Partners, an organization focused on affordable housing issues, I attended a meeting of the Mayor of Oakland’s Housing Cabinet. A mix of city housing department staff and representatives from affordable housing nonprofits spent the two-hour meeting discussing the importance and challenges of incorporating racial equity components into the city’s affordable housing program guidelines. Though they weren’t able to come to a conclusive decision in two hours, and although people disagreed on the timing and implementation method, everyone was incredibly passionate and utilized their experience to offer new ideas.

I was deeply inspired and motivated by what I saw in that room. As I reflected on what was most meaningful to me this summer, I kept coming back to the constant excitement I felt spending all summer around people who shared my passion for and my perspective on the inextricable link between housing policy and racial justice.

As a regional housing policy intern, I spent most of my summer drafting legislative language and conducting research tasks for AB 1487, state legislation that enables the creation of a Bay Area Housing Finance Authority for the entire nine-county (and 101-city) region. I learned that laws are, in fact, written on Word software. I learned about the political and logistical opportunities and challenges of coordinating an affordable housing strategy at the regional level. I began developing a regional perspective, learning comparatively about the unique housing needs across different jurisdictions; the affordable housing landscape is entirely different between Oakland, Palo Alto, Fairfield, and Sonoma in the context of fire recovery, yet we worked to design a framework for a regional authority that will supplement collective needs and work for everyone. I attended convenings with people from around the Bay Area who were trying to work together to solve our regional problems.

Having grown up in the Bay Area, my work in housing justice at the local level has always felt personal. I am witnessing my friends from high school make decisions about whether or not they can afford to live on the Peninsula, while college friends who have graduated join the ranks of new tenants who are both drawn into and disgusted by the contradictions of Silicon Valley culture. Working in the financial district in San Francisco this summer gave me a new perspective into this culture, as I witnessed who actually lives and works in this region. I know that I bear unique witness to this dual perspective, the “old” and the “new.”

However, I did not anticipate that working on a state bill for a regional housing authority would make me reflect on what this entire region means to me personally. I knew that I had a deep commitment to justice in the county I grew up in, but working on housing at the regional level reframed the geographies that I include in my “home.” If custodial staff working at Stanford are commuting from Antioch, I must consider Antioch to be a part of our home. I realized that if I am going to fight towards an inclusive Bay Area – against the racial and socioeconomic segregation that occurs on a regional level – I needed to make my personal definition of home inclusive of the entire region. The futures of Richmond and Marin, for example, or Oakland and Menlo Park, are deeply connected. I now feel that I have a stake in these connections as a part of my dedication to equity in the place I call home.

Nani Friedman (she/her), ’20 grew up in Belmont, CA. With a major in Urban Studies and a minor in Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity, Nani applies her studies to affordable housing issues. She has participated in an Urban Summer Fellowship (2019) and a Community-Based Research Fellowship (2017) through Cardinal Quarter. She is a founding member of the Stanford Coalition for Planning an Equitable 2035 (SCoPE 2035), a housing justice activism group at Stanford.