Category: Cardinal Commitment

My Most Important Lesson

By Thomas Allen Wehner, ’20, MS ’21

When I first started as a tutor with the High School Support Initiative (HSSI) freshman year, I didn’t realize the depth of the program and how much it would mean to me. I signed up after getting an email about the program because I liked tutoring and it sounded like a good cause. I joined HSSI as a tutor going out to my school site once a week. I was barely aware of the complexities of the program, the intricacies of ethical service, and the depth of how my identities interacted with the complex histories and systems at play in the education system. I had a lot to learn.

At the end of freshman year, I became an HSSI fellow and spent the next three years working with and learning from the incredible team. As a fellow, I was part of the program staff, with expanded responsibilities to support the tutors and program. As a team, we worked with Stanford students, analyzed feedback, hosted workshops, discussed articles and program changes, filled in spreadsheets, tracked attendance, and went out every week to maintain our anchor in the most important work by tutoring high school students.

This experience sparked my interest in education, organizational behavior, and nonprofit work. I had joined HSSI because of its focus on working with high school youth, but working as an HSSI fellow helped me discover that I was even more interested in learning how to develop the organization and volunteers to better serve and collaborate with youth and community partners. This insight helped guide my future plans, highlighted what talents I have to use in collaboration with others to build a better world, and revealed what skills I still need to develop.

Every experience with HSSI pushed me forward as a person – whether building facilitation skills with volunteers, learning the power and shortcomings of the Principles of Ethical and Effective Service, or better understanding how to be an ally as a person of privilege in the fight for educational equity.

The time I spent with the HSSI team added so many dimensions to my Stanford experience, and I consider it to be the most important part of my education here. Beyond fostering a set of technical skills, this experience helped me learn about myself and understand my journey to being a better friend, ally, coworker, volunteer, leader, and person. I am forever grateful to Sophia Kim, our wonderful program director and mentor, and the rest of the HSSI family for this incredible experience.

Originally from Highland Park, IL, Thomas Allen Wehner, ’20, MS ’21, studies electrical engineering at Stanford. In addition to serving with the High School Support Initiative (HSSI) for all four years of his undergraduate career, he has been involved in the campus theater scene, most recently as the executive producer of Ram’s Head.

Global Engagement: Engineering Solutions for Sustainability

By Adam Nayak, ’22

Ever since I was little, I have been fascinated with water. I grew up four blocks from Johnson Creek, a local stream in southeast Portland, Oregon. My mom took me down to the park to play in the water, letting the currents wrap around my legs as I searched for tadpoles and capered with dragonflies.

Each month, my family would wake up early in the morning to work with our local watershed council, removing invasive species, planting native species, and picking up trash around the stream.

It was here that my younger sister and I learned about the great salmon migration. I remember being fascinated with the fish: their perseverance, determination, and tenacity, traversing upstream to their birthplace to continue their lineage. As a boy, I was always searching for salmon, but as an urban stream, Johnson Creek faced serious water-quality challenges due to a history of pollution, and I was never able to find any fish.

As I grew older, I developed an interest in the science behind water treatment and ecological systems, looking for solutions to problems of contaminated stormwater and habitat loss. Volunteering with the Johnson Creek Watershed Council was one of my most rewarding experiences, instilling in me a value for public service and community engagement that has grown with me at Stanford.

Through my involvement in Engineers for a Sustainable World (ESW), a Cardinal Commitment student organization, I have been able to pair my interest in environmental conservation with engineering practice. In particular, I worked on a small team of students during a two-quarter Cardinal Course to design and prototype sustainable infrastructure solutions in Chavín de Huántar, Perú, an archaeological site in the Andes Mountains. Through the Cardinal Quarter program, I traveled to Perú with my team this past summer to implement the project and promote cultural conservation.

Our green roofs and modular tensile structures were designed as a new approach to flood mitigation in a rural setting, with a focus on aesthetic integration of roofing structures at a culturally significant site. This opportunity not only strengthened my Spanish language and communication skills, it allowed me to collaborate with engineers and community members, as well as to learn about engineering practices in the context of a different culture and setting.

Service is powerful to me because it establishes a sense of community and belonging. As a student who is passionate about equity and inclusion, I hope to work on sustainability projects in diverse communities worldwide. The experience in Perú has enhanced my ability to collaborate on a team that spans cultural backgrounds and has reaffirmed my passion for public service projects.

Now as a sophomore, I co-lead international ESW projects focused on sustainable engineering and equitable development. They have brought me back to the theme of water, leading a project with community partners in Ghana focused on organic waste mitigation and water treatment through biochar production for carbon filtration.

For me, service involves building relationships and working collaboratively, whether internationally with an organization like el Ministerio del Cultura de Perú, or locally with the Johnson Creek Watershed Council. Both experiences involved a long-term commitment to addressing community needs. From these experiences, I have come to focus on promoting equitable access to resources for all communities, regardless of background. Looking forward, I hope to continue my work in sustainable development as an environmental engineer, focusing on clean water and equity practices in the public sector.

Adam Nayak, ’22, studies civil and environmental engineering. Originally from Portland, Oregon, Adam’s childhood interest in environmental sustainability has led him to pursue a Cardinal Quarter in Perú, enroll in Cardinal Courses, make a Cardinal Commitment with Engineers for a Sustainable World, and serve as a Cardinal Service peer advisor. Adam has also been involved in the Multiracial Identified Community at Stanford; Stanford Strategies for Ecology Education, Diversity, and Sustainability; Students for the Liberation of All People; and Students for a Sustainable Stanford.

$5 Shuttle Buses to the Airport

By Kelsie Wysong, ’20

I have the pretty unique experience of getting into Stanford off of the waitlist. I remember actually getting a call from my admissions officer, rather than just an email or a letter sent to my house. He spoke with me for almost two hours about whether I should give up my spot at another school in order to take one at Stanford. As a first generation, low income (FLI) student, one of my main concerns about Stanford was money. I remember asking him how most students get to and from the airport when flying home over the holidays.

“Well, I think most students just Uber,” he responded.

Growing up in Metro Detroit, I’d never considered Uber as a transportation option. Even if Uber was more widespread in the Bay Area, I didn’t trust a random stranger to drive me, nor did I have a credit card to open an account. Even then, it seemed to me that Stanford could do more to help its students with getting to and from home.

Stanford is situated almost equally between the San Francisco and San Jose airports. While students have the opportunity to choose between the airports to find the cheapest flights, having multiple departure points makes it much harder to coordinate rides with friends or dorm mates. As a result, students take thousands of costly and carbon-filled individual trips to the airports.

In the spring of 2019, seeing a need to provide students with a more sustainable solution, the Associated Students of Stanford University (ASSU) teamed up with Students for a Sustainable Stanford (SSS) to provide $5 bus shuttles to the airports during spring break. They sold 76 tickets and about half of those students checked in. While the initial trial was small, students who took the shuttles reported satisfaction with the price and drop off points.

I joined the project shortly after the trial run, having been involved with various other sustainability projects on campus. In the fall, we decided to offer the shuttles again to take students to and from the airport for Thanksgiving break. This second iteration sold out. Of the 225 tickets sold, 81% of people actually rode the buses. For winter break, we added more seats on each bus, and even included an additional third day of shuttles. Again, we saw an 81% turn out rate of the 375 tickets we sold.

So far, our shuttle program has been a huge success on campus. Student reviews have been overwhelmingly positive. In addition, our bus shuttles saved students thousands of dollars in Uber rides and prevented over 2,000 lbs. of CO2 pollution. We are excited to continue to learn from the spring break shuttles planned for later this quarter.

This project has truly been one of the highlights of my Stanford career, as I am able to help meet the needs of both the FLI community and the sustainability community. I believe that most students are looking for ways to leave Stanford better than they found it, and this project is my chance at contributing to that dream. When the next person debating on whether or not to attend Stanford asks how they will be expected to travel to and from home, ASSU and SSS will be able to give a sustainable, inclusive answer that directly shows how Stanford students provide solutions for their peers.

Originally from Wayne, MI, Kelsie Wysong, ’20, studies bioengineering at Stanford. Outside of the classroom, Kelsie is the ASSU co-director for environmental justice and sustainability and a member of the Senior Class Cabinet. Through a partnership between the ASSU and Students for a Sustainable Stanford, Kelsie helps organize shuttles to take students to the airport over breaks in order to reduce carbon emissions and save money. They also serve as the vice president of TapTh@T, Stanford’s tap dance performance group.

Serving Those Who Have Served: 25 Years of United Students for Veterans’ Health

By Erika DePalatis, ’19

It all began in 1994.

While volunteering in the Alzheimer’s Ward of the Palo Alto Veterans Affairs Administration Hospital, Vance Vanier, a Stanford undergraduate studying economics and political science, noticed that many of the patients were suffering from loneliness.

With little connection to the outside world, many of these veterans rarely had the opportunity to interact with others, outside occasional family visits and planned events. Worse still, patients in this long-term care ward often experienced cognitive impairments such as Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia, which can make patients feel confused or distressed when isolated.

These veterans had served their community; Vanier wanted to help organize their community to serve them. Rallying forty other volunteers, Vanier founded United Students for Veterans’ Health (USVH) with the goal of building caring, meaningful relationships between students and long-term care patients in Veterans Affairs (VA) Hospitals. Vanier’s brother, Andre, launched USVH’s national expansion the following quarter and thereafter expanded his role as the chair of USVH’s National Advisory Board.

Over the years, USVH has expanded across the United States, becoming one of the first nationwide student organizations connecting students with hospitalized veterans. Chapters at the University of Southern California and University of Alabama were founded several years ago, and the group’s sustained growth still continues: earlier this year, a new USVH chapter was established at the University of San Francisco, supported by the diligent efforts of USVH’s national co-presidents, Stanford students Komal Kumar, ’20, and Zane Norville, ’21.

“Our chapter in San Francisco has been a long time coming. The veteran population at the SFVA hospital is conveniently located near two undergraduate universities, San Francisco State University and the University of San Francisco. …[W]e are proud to say the program is launching now, with a group of six dedicated pilot student volunteers,” explains Kumar.

The original Stanford chapter of USVH, however, has never forgotten the local need which first started this national organization. Each fall, USVH recruits new volunteers to serve veterans at the Menlo Park Veterans Affairs Hospital (MPVA). Student volunteers visit the hospital’s long term care facility, where many of the veterans have been living for several years, and, through weekly visits, build meaningful friendships. The group’s connection with the local veteran community has only grown during its many years of operation, as evidenced by the group hosting an increasing number of events at the hospital each quarter, including an event this past fall that attracted the highest veteran turnout in USVH’s history, with over 25 veterans in attendance.

“The hospital can be a dismal and lonely place for some of the veterans,” explains USVH alumni John Rodgers, ’19. “Although it could feel like a small thing to visit the VA once a week, listening to someone’s story and really trying to get to know them can go a long way toward improving their time in the hospital.”

In addition to the relationships built between USVH participants and veterans, USVH plays an important role on campus by hosting educational events that inform the campus community about issues affecting veterans. For example, USVH partnered with the Stanford United Veterans Association (SUVA) in October 2019 to host two SUVA representatives and a VA psychiatrist for a panel discussion on veterans’ portrayal in the media.

This year, USVH celebrates its 25th year of partnership with the Haas Center for Public Service, during which time USVH volunteers have reported serving over 50,000 hours at the MPVA. In partnership with the Haas Center, USVH honors students who sustain their involvement with the group for at least three quarters by offering them a Cardinal Commitment certification. Since the launch of the Cardinal Commitment program just two years ago, 16 USVH students have received this certificate.

The thought of over-scheduled Stanford students consistently making time each week to visit elderly veterans might strike some as surprising; but Kelly Beck-Sordi, Haas Center Associate Director and Director of Cardinal Commitment, would explain that, instead, the dedication of USVH student volunteers is just one example of the growing culture of service on campus.

“Every year, hundreds of Stanford students make year-long commitments to serve with student groups, community organizations, and campus programs, from teaching local youth how to code to advocating for workers’ rights,” Beck-Sordi explains. “USVH has been very successful in engaging students over the years, and that’s because students care about serving those who have served our country. Students want to give back.”

Erika DePalatis, ’19, serves as the Communications Coordinator at the Haas Center for Public Service. Prior to her work at Haas, Erika studied English and Italian at Stanford and worked as an oral communications tutor at the Hume Center for Writing and Speaking. Her role allows her to elevate student stories of service and connect Stanford students with service opportunities.

Hidden in Plain Sight: Deconstructing the Mental Health Stigma

By Anika Sinha, ’21

Content Warning: This post contains information related to self harm and mental illness that can be difficult to review. Please make use of campus resources such as Vaden Health Center’s Counseling & Psychological Services and The Bridge Peer Counseling Center to support your safety and well-being.

“I cut myself pretty often. I want to stop but I can’t. How do you stop?” My teaching partner and I stared at this card for longer than usual, then glanced at each other, unsure of how to proceed.

I am a classroom teacher for Health Education for Life, Partnerships for Kids (HELP4Kids). Every Friday, I teach health education to sixth graders at a local middle school. Topics include mental health and wellness, exercise, nutrition, drugs and alcohol, and sleep. Most of my days in the classroom are full of giggles and interrogations about the college experience. Questions can range from: “What classes are you taking?” to “How often do people get drunk?” HELP4Kids lets me escape the Stanford bubble for a brief hour and immerse myself in the colorful world of a middle school classroom. Regardless of my mood on campus, I trust the kids to bring a smile to my face… but this is not always the reality.

At the end of every class, we hand out notecards to the students, so they can ask anonymously any questions they may be uncomfortable to ask in front of the class. The topics we discuss can be quite sensitive and personal, so we want to give space for deeper discussions. Some of the notecards are random sketches pulled out of wild 11-year-old imaginations, some are simple “thank you’s,” and some even contain memes. However, the majority include thoughtful comments or questions about the day’s lesson.

The day we taught a lesson about mental health, I knew we would receive some sensitive questions. But I was still stunned and unprepared to find out that one of my students was struggling so deeply. This indicated my own naiveté. How could someone so young be afflicted to the point of hurting themselves? I thought. After reflecting for a while, I realized that this very mindset was part of the problem. Instead of marveling at how problems like this could even exist, I needed to consider the underlying systemic issues perpetuating my surprise. This child had obviously been hiding this issue. Without the notecards we passed out, they would not have had a platform to speak up. Their reluctance to ask for help ultimately boils down to the stigma attached to mental health issues, a problem that ravages our society.

After reading the notecard, my co-teacher and I reached out to the classroom teacher and school nurse immediately to address the situation. They informed us that they knew the student who wrote the note, and would follow up imminently to ensure they received proper care.

Experiences like this one have shown me that reducing stigma around mental illness is of paramount importance, especially when it comes to adolescents. More notecards from the students in HELP4Kids revealed similar themes, and those were just from the ones who were brave enough to speak up.

I know I am just barely scratching the surface of this issue, but I am doing what I can to reduce this stigma on campus. As a residential assistant and co-president of Stanford Mental Health Outreach, I have been committed to normalizing conversations about mental illness through speaker panels, mental health short films, and fostering vulnerability with my residents. The more these conversations occur, the more students will be able to admit to themselves and to others that they are struggling. This is the first step toward healthily managing life with a mental illness.

My experiences are teaching me that mental illness is relentless: nobody—no matter their age, gender, career, income, education—is given a free pass. If someone seems too young or too accomplished to be battling with it internally, I need to think again. To combat stigma, we need to foster platforms where people can speak openly about their struggles, without fear of judgement… and, most importantly, with the promise of support.

Anika Sinha, ’21, is majoring in human biology with a minor in psychology. In addition to working with youth through HELP4Kids and Peer Health Exchange, Anika is involved in Student Clinical Opportunities for Premedical Experience (SCOPE) and Stanford Mental Health Outreach (SMHO). You can find Anika at Branner Hall as a resident assistant, or at the Haas Center for Public Service, where she serves as a Cardinal Service Peer Advisor.

Learning through Service

By Kathryn Rydberg, ’19

When I entered the sixth grade, I switched to a new school. As the new girl, I was confronted by new classmates, new surroundings, and new classes—including a class called “Service Learning,” which involved reading books to second graders at a nearby charter school. Initially, I was confused as to why this program was called Service Learning. Since the goal of the class was to help the second-graders learn to read, I figured that a more accurate name might be “Service Teaching.” By the end of the year, however, I realized that the program had taught me as well. I came to understand how challenging it can be to teach a student something new, but more importantly, the experience of going to the school and interacting with the younger students exposed me to an environment and community that I would not have otherwise known. Though this experience happened when I was much younger, the realization that service initiatives can be beneficial to the people doing service as well as to those in need stuck with me.

Fast forward to my first year at Stanford, when I came across a club that seemed to be focused on making the world a better place while teaching students valuable professional skills at the same time. As it turned out, professional skills were just the tip of the iceberg of what my involvement with the Stanford Social Entrepreneurial Students’ Association (SENSA) would give me. Meaningful friendships, leadership skills, professional connections, experience speaking at an international conference with hundreds of attendees: these are all things I would never have had if not for SENSA.

I learned that not everyone agrees on what social entrepreneurship is, but that in general, it means applying entrepreneurial strategies in an effort to make positive, sustainable social change. Per that goal, social entrepreneurs recognize the crucial fact that if a business is economically sustainable, then it is able to make a more sustainable social impact. Similarly, organizations are more effective if smart, talented people continue to invest their efforts into them over time. Opportunities for learning and growth provide an incentive for people to continue their involvement with the organization—and that means that the organization can continue doing important work.

I saw this firsthand during a time of great turnover within SENSA. If students felt that they were not benefiting from their membership, they would quickly cease coming to meetings or replying to messages. Beyond the satisfaction of helping others, every organization has learning opportunities to offer its members: communication skills, teamwork, or leadership of an event or program. Though I was learning a great deal through my involvement with SENSA, I realized that others might lack access to these opportunities for growth. As a result, I worked to restructure SENSA to ensure that every member was able to take ownership of their service learning.

I believe that this lesson could also benefit social enterprises. Of course, the goal of many social enterprises is to put themselves out of business by solving the problem that they exist to address, but many social problems are so complicated that they will likely not be solved within our lifetimes. Therefore, the issue of talent should be viewed in the same terms as financial sustainability. Social enterprises should aim to keep employees and others who interact with their organizations engaged by offering benefits beyond the satisfaction of helping others. When the financial model and the “people model” are both sustainable, then an organization can focus fully on solving the complex issues that afflict our society.

Kathryn Morgan Rydberg has a BA in American Studies and a minor in political science. Throughout her undergraduate career, Kathryn was actively involved in the Stanford Social Entrepreneurial Students Association (SENSA) and became president and the Cardinal Commitment mentor of the organization. As a senior, she was a member of the Public Service Honors Society and the Pi Sigma Alpha Political Science Honors Society. She also served as marshal for Kappa Kappa Gamma and participated in the Stanford Marketing Group.

Reflecting on Four Years of Cardinal Service

By Callan Showers, ’19

The Cardinal Service initiative began my freshman year, in the fall of 2015. I am so thankful I made a lasting service commitment right away, by joining a Cardinal Commitment organization called Women and Youth Supporting Each Other (WYSE).

The Stanford women in WYSE facilitate weekly mentorship sessions for middle school girls in East Palo Alto and discuss topics like puberty, women’s empowerment, race and discrimination, and sexual health.

I was persuaded to apply because it seemed like a way for me to expand my sense of community and purpose at and around Stanford. This couldn’t have been truer. Engaging with the East Palo Alto community and its middle schoolers through WYSE has taught me innumerable lessons about cultural humility, community action, education justice, and leadership.

I also had the chance to engage with the broader Bay Area through the Cardinal Course, From Gold Rush to Google Bus: History of San Francisco. We worked with a community partner to identify little-known stories about the city’s history and write articles for an online historical database. I got to nurture intellectual interests through experiences such as digging through archives in the San Francisco Public Library, while also contributing to a community-based project with lasting impact. It also helped me realize that you don’t have to be from a place to help shape its history.

While these experiences connected me to parts of the local area, Cardinal Service programs also helped me serve in the place I have always called home: Minnesota.

The summer after my sophomore year, I received the Advancing Gender Equity Fellowship from the Haas Center and Women’s Community Center to work as a legal intern at Gender Justice, a public interest law firm in St. Paul. Gender Justice represents clients who have experienced gender discrimination or sexual harassment, and I got an inside look into legal proceedings such as depositions, while also getting the chance to draft policy advocacy memos and see the inner workings of a nonprofit.

This Cardinal Quarter inspired me to pursue public interest law because of how well it fit my skills and my desire to make change. I am pursuing a two-year position as a paralegal at a civil rights law firm in Washington, D.C. I truly believe without the values of community-engaged learning experiences and the way I saw my personal and professional values and skills align at Gender Justice, I would be less prepared to enter into this work and my life beyond.

Callan Showers, ’19, was in the first class at Stanford to experience four years of Cardinal Service. She co-led the student organization Women and Youth Supporting Each Other (WYSE). Callan also completed a Cardinal Quarter with Gender Justice, a nonprofit law firm, and a Cardinal Quarter from the Bill Lane Center for the American West serving with the French cinema house Galatée Films.

Callan Showers, ’19, was in the first class at Stanford to experience four years of Cardinal Service. She co-led the student organization Women and Youth Supporting Each Other (WYSE). Callan also completed a Cardinal Quarter with Gender Justice, a nonprofit law firm, and a Cardinal Quarter from the Bill Lane Center for the American West serving with the French cinema house Galatée Films.

What End-of-Life Care Taught Me About Medicine Beyond Medication

By Jonathan X. Wang, ’19, MS ’19

I remember how Frank loved jazz. How he smiled whenever I mentioned his wife or his three daughters. The stain on the corner of his checkered shirt, the slight bulge in his belly, the tan khakis he always wore.

But I also remember how frail his aging hands were. How Alzheimer’s took his ability to remember his favorite song. How his face would fall at the end of our weekly visits. I remember his last whisper to me that echoes in my head months after his death.

Frank, like my other hospice patients, taught me that medicine isn’t only about life expectancies, surgeries, or prescriptions. It’s about Nate, a teen with HIV whose main concern is whether he’ll ever make friends at school; or Jacob, who wants to spend his remaining days with his three daughters, not at a clinic taking a barrage of medical tests.

I first started volunteering in hospice the summer before coming to Stanford, with some encouragement from my older sister and a book I read, The Empathy Exams by Leslie Jamison. The patients I met showed me the value of care beyond data and diagnosis, beyond literature and calculations. I have seen a patient’s eyes light up over a conversation about their poetry collection, their wife, their three kids. I’ve also sat with patients as they came to a peaceful end or violently struggled to keep their autonomy. These experiences have taught me that empathy can be like a clinical skill—we strengthen it when we go beyond routine pleasantries, and we treat with it by listening with intent and bringing difficulties to light.

Frank’s diagnosis of Alzheimer’s meant that during our time together, he lost memories of who he was. It meant he was going to forget our visits. He was going to forget my name. I know many of these stories are sad, and some did not have happy endings. But these stories inform my resolve to make sure that in the future we find ways to change the ending for people like Frank.

Inspired by my experiences in hospice, I reached out to Dr. VJ Periyakoil, the director of Palliative Care Training at Stanford Hospital. Under her guidance, Anthony Milki, ’18; Yong-hun Kim, ’19; and I established an organization in 2016 that works closely with the elderly community to engage students in compassionate care and spread awareness of the challenges facing our growing elderly population: Stanford Undergraduate Hospice and Palliative Care (SUHPaC).

Through SUHPaC, I have seen how working with patients at the end of their lives fosters love and respect for others. I have witnessed the transformation of our members into caregivers as they discover that medicine is more than just a pill. Founding the organization is the thing I am proudest to have done at Stanford. Someday, I hope to shake the hands of a hospice patient, not as a young man unsure of his future, but as a confident, learned, and caring individual in a white coat, extending a hand to help.

Jon Wang, ’19, is a computational biology major and coterminal master’s student in biomedical informatics. He is a member of the Public Service Honor Society, a year-long cohort of seniors that provides students the opportunity to reflect on their public service and develop their civic leadership identities. At Stanford, Jon has been involved in Stanford Emergency Medical Services, Golden Gate Science Olympiad, AI and Cancer Biology Research, and Stanford Health Innovation. He is from Roseville, Minnesota.

Launching The A(bilities) Hub Initiative

By Zina Jawadi, ’18, MS ’19

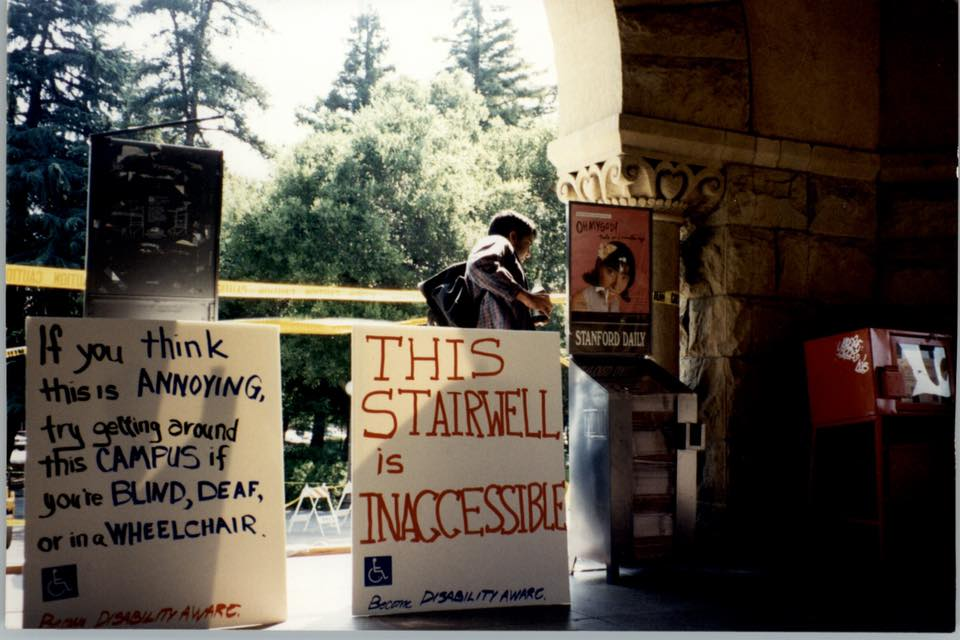

Disability advocacy efforts have been vibrant at Stanford for decades, and over the past few years, students with disabilities have resumed advocating for a disability campus center.

In 2013, Vivian Wong, ’12, realized that there was no disability community space or student organization at Stanford for students with disabilities.

She helped create a new position in the ASSU Executive Cabinet and worked with Krystal Le, ’14, to found Power2ACT, a much-needed student organization that provided a safe space for students with visible and hidden disabilities.

When I arrived at Stanford in 2014, I saw that people with disabilities still lacked a physical space. I had just worked with my high school’s administration to found a disability awareness program and thought I could draw on this experience to help make a meaningful impact at Stanford.

I am a member of several minority groups as a hard-of-hearing, Iraqi American, second-generation immigrant. My passion for disability advocacy began in the eighth grade, driving me to compete in more than 30 Original Oratory competitions and to join the Hearing Loss Association of America, California State Association. At Stanford, the skills from my nonprofit board involvement and my public speaking experience came in handy.

During my sophomore year, former Power2ACT president and ASSU Executive Cabinet member Chris Connolly, ’15, and Kartik Sawhney, ’18, reached out to help me revive the pursuit of a campus center with the ASSU Executive team. Together, we communicated to students, faculty, and administrators about the need for a physical space on campus.

I am often asked why it is important for a community to have physical space at the Farm. A physical space will allow students without disabilities to think about disability, increasing the visibility of disability and emphasizing the disability community’s place at Stanford.

In November 2017, the A(bilities) Hub Initiative was launched in conjunction with the 2017-2018 Disability Awareness Week. We were appointed an official staff advisor, Carleigh Kude, and established a student-led committee for the A-Hub.

In launching the A-Hub, I discovered the many paths that our members take to join our community, including advocacy, disability studies, personal reasons, or a family member’s experiences. Working with them, I learned how a few individuals with shared advocacy goals can make a community stronger and that unifying individual efforts can multiply the effects.

Currently, the A-Hub is a temporary space, and we are still working toward a long-term solution: an established community center with a full-time director.

Zina Jawadi is a student advocate for disabilities rights at and outside of Stanford. Zina supported the launch of the Abilities Hub in 2017 and the formation of the Stanford Disability Initiative in 2017, for which she continues to serve as co-chair. Zina was the president of Power2ACT in 2016-17 and was an ASSU Executive Cabinet member in 2016-17 and 2017-18. Outside of Stanford, Zina is active in the Hearing Loss Association of America – California State Association, serving as board member since 2013 and president since 2015. Zina is a member of the Haas Public Service Honor Society. She is from the San Francisco Bay Area.

Advocating for patients and policy change

By Brian Kaplun, ’18 (Human Biology), MS ’18 (Management Science & Engineering)

I’ve wanted to be a doctor ever since I was a kid, but it was an experience as a research assistant at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles right before coming to Stanford that showed me there is more to healthcare than a doctor’s visit. There, I met a small boy who had gone blind due to his family’s lack of consistent access to healthcare—an entirely preventable loss. Based on this experience, and the many lessons on injustice and inequity to come, my coursework, advocacy, and service over the last four years have all been part of a deeply held commitment to addressing healthcare disparities.

I started volunteering at the student-run Arbor Free Clinic my first quarter at Stanford as a Bridge to Care counselor. It was my job to find patients what the clinic couldn’t provide—from health insurance and a regular doctor to temporary housing, legal assistance, and job training. I learned how a difficult diagnosis or untreated illness could impact every aspect of one’s life, and about the potentially harmful interplay between health and sociopolitical factors—including from far too many undocumented families scared to seek healthcare out of fear of being separated and torn apart.

This was—and still is—the hardest job I’ve ever had, but it was the first time I felt like I had the knowledge base to help others. However, even after three years on the team, the sheer complexity and gaps in the healthcare system and the broader safety net meant that often our patients couldn’t get the help they needed.

I worked my way up to become clinic manager, overseeing more than 100 undergraduate and medical student volunteers. As the primary liaison to other Bay Area community health centers and agencies, I worked to strengthen collaborations to provide patient resources, including up-to-date information on topics such as immigration assistance, domestic violence resources, and pro-bono surgery options. Most importantly, in my successes and failures as a volunteer and manager, I learned that as an outsider to the communities we served, I needed to recognize my privileges and biases; the most important thing I could do was know when to listen, and to stay humble and empathetic.

As a gay man, I have struggled with less-than-inclusive care, and LGBTQ+ advocacy has been an important part of my passion for healthcare equity.

At Arbor Free Clinic, I co-led the Queer Health Initiative, a multi-year project to systematically improve services and care for LGBTQ+ people. I also served with the Human Rights Campaign on the Healthcare Equality Index, a tool focusing on inclusive hospital policies, and at Pangaea Global AIDS as a Huffington Pride Cardinal Quarter Fellow, studying the HIV policy landscape for gay men and trans women in Zimbabwe.

While one-on-one patient interactions reaffirmed my goal to be a physician, through Stanford courses on racial and ethnic health disparities, the American healthcare system, and policy analysis, I learned about the broader policy and social landscape that leaves so many patients behind. Last summer, as a Sand Hill Foundation Cardinal Quarter Fellow at Kaiser Family Foundation, I applied this learning to writing policy analysis and issue briefs about changes to the Affordable Care Act and the state of the HIV epidemic for gay and bisexual men.

In the coming year, as a 2018 John Gardner Public Service Fellow, I will staff the Democratic health policy team for the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee in the U.S. Senate, with Deputy Health Policy Director Andi Fristedt as my mentor. This committee is the battleground for many of the fights over Affordable Care Act repeal, healthcare costs, and reproductive justice, and where legislation to curb the opioid epidemic is taking shape, and I’m excited to dive into these important efforts. Following the fellowship, I will pursue a medical degree at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

At Stanford it was service that affirmed, over and over, the issues I cared about and the ways I needed to be involved. Through my Cardinal Commitment, I learned how to channel my frustration with inequity into a constructive desire to do more. As I look toward life after Stanford, I hope to continue working in both the clinical and systemic aspects of health—as a doctor healing individual patients, and as a policymaker and advocate working on the broader factors that affect their wellbeing.

Brian Kaplun was one of more than 300 students who declared a Cardinal Commitment in 2017–18.